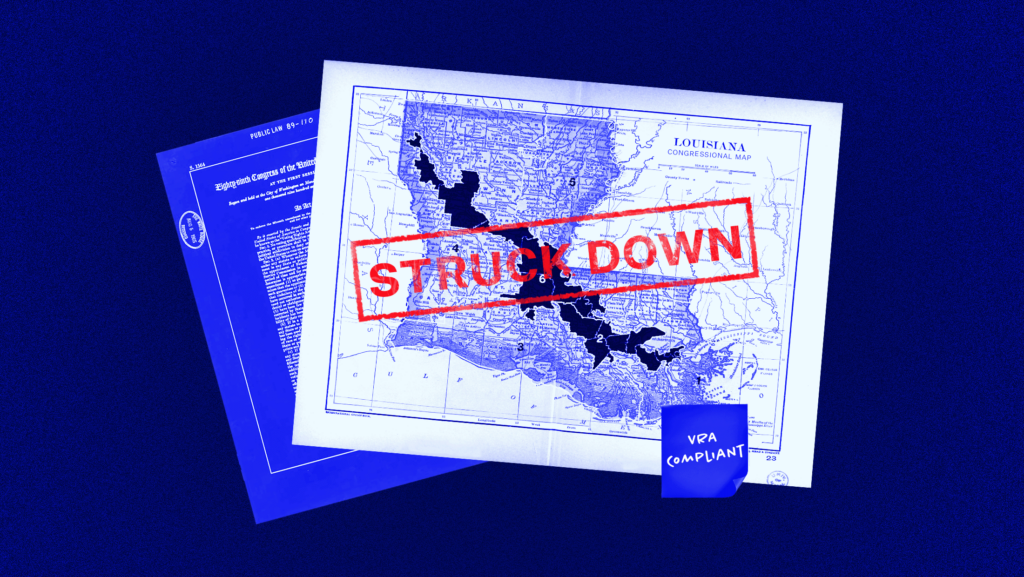

Left Without a Congressional Map, Black Louisiana Voters Ask Supreme Court for Help

In January, Louisiana’s Republican governor signed into law a congressional map featuring two majority-Black districts, seemingly ending a nearly two-year-long redistricting battle over fair representation for Black voters in the state.

The congressional map — which increases the Black makeup of the state’s 6th Congressional District, stretching from Caddo Parish to East Baton Rouge Parish — cleared the Legislature and after its passage was lauded by voting rights advocates as a step forward for the Pelican State.

But last week, a federal district court struck down the map for being an unconstitutional racial gerrymander. The opinion comes just weeks before May 15, which is the deadline for when the state says it needs an approved congressional map in place ahead of the 2024 elections.

Now, a group of Black voters and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund are asking the U.S. Supreme Court to review the lower court ruling — and quickly. “It’s time for the Supreme Court to put an end to this,” Jared Evans, senior policy counsel at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, told Democracy Docket in a phone interview. “We’ve been back and forth for two years.”

Evans’s team is asking the Court to allow Louisiana to proceed with the new map for this fall’s election. That request entailed asking the Court to pause the district court decision blocking the map — even if it decides to address other aspects of the district court opinion at a later date. On Friday, the district court denied a motion to pause its own ruling while litigation continues.

Louisiana now bears an unfortunate distinction. It’s “the only state in the country that does not have a map in place for this fall’s congressional election,” Evans said.

The case marks a racial gerrymander ‘reboot.’

The district court ruling stems from a lawsuit filed on behalf of 12 individuals who identified themselves as “non-African American voters.” A review of some of the plaintiffs’ social media accounts by Democracy Docket shows that at least a few of the individuals are white. The lawsuit sought to block the map, alleging that it’s an unconstitutional racial gerrymander in violation of the 14th and 15th Amendments.

The plaintiffs argue that throughout the redrawing process, the state’s purpose was clear: “segregate voters based entirely on their races and create two majority-African American voting districts and four majority non-African American districts, without regard for any traditional redistricting criteria,” according to the complaint.

By consolidating African American voters into two districts stretching hundreds of miles in length across Louisiana, the state, the complaint states, engaged in “textbook racial gerrymandering and violated the U.S. Constitution.”

The congressional map that the plaintiffs challenged was created to remedy a previous version of the map after the courts found that the original map — which only had one majority-Black district — violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

The issue here is that, according to Supreme Court precedent, race can’t play a predominant factor in the design of a district, unless the state can prove that it has a compelling reason. “If [plaintiffs meet] the burden of showing race played the predominant factor in the design of a district, the district must then survive strict scrutiny,” the three-judge panel wrote.

While it may seem unusual that a group of non-Black individuals are alleging an unconstitutional racial gerrymander, Michael Li, senior counsel for the Brennan Center’s Democracy Program, told Democracy Docket in a phone interview that the plaintiffs’ case is reminiscent of the racial gerrymander lawsuits of the 90s, spearheaded mostly by white plaintiffs.

“The origins of racial gerrymandering as a constitutional doctrine are in claims brought by white voters,” Li said. “But in more recent decades, they’ve been brought increasingly by people of color to fight discriminatory maps.”

In Shaw v. Reno, for example, North Carolina voters challenged the state’s congressional map, alleging an unconstitutional gerrymander over the creation of two majority-Black districts. The 1993 case established the legal principle that racial considerations in redistricting are subject to strict scrutiny by courts. The plaintiffs in this case were five white Durham County residents.

“In the same way that we’re having reboots of 1990s TV shows,” Li said, “now there’s a reboot of racial gerrymander claims brought by white voters.”

Louisiana’s 6th Congressional District is at issue.

In explaining its decision, the district court panel cited Thornburg v. Gingles, a 1986 ruling that established what’s known as the Gingles factors, a test that courts have applied for decades. The Gingles test “requires the creation of a majority-minority district” only when three preconditions are met:

- The minority group must be large and compact enough to constitute a majority in a “reasonably configured district,”

- The minority group must be politically cohesive and

- A majority group must vote sufficiently as a bloc to enable it to usually defeat the minority group’s preferred candidate.

In this case, the defendant — the state — has “simply not met its burden of showing that District 6 satisfies the first Gingles factor – that the ‘minority group [is] sufficiently large and [geographically] compact to constitute a majority in a reasonably configured district,’” the judges wrote.

But Evans took issue with the court’s conclusion about how much race was a factor in redrawing. He pointed to testimony from state lawmakers who were present for the mapdrawing process.

“We had members of the legislature, [state] Sen. [Roy] Duplessis (D), and Rep. [Mandie] Landry (D) testify that politics drove the drawing of this map,” Evans said. “The record was full and robust on how politics was the overriding factor.”

The redrawn 6th Congressional District encompasses an area currently represented by U.S. Rep Garret Graves (R), who expressed his displeasure at the changes, which would likely undermine his chances of getting reelected and give Democrats an additional seat in Congress.

Voters wait for the Supreme Court to weigh in.

Li noted that, procedurally, the court could have issued a partial ruling that allowed the map to remain in place for the 2024 elections while the lawsuit’s claims move forward in court. Evans expressed a similar view, and cited an Alabama case — Allen v. Milligan — in which that course of action was taken.

In the Alabama case, voters and nonprofit organizations sued Alabama over its congressional map in 2021. After a district court blocked the map and ordered the creation of a new one, the U.S. Supreme Court paused the order, meaning that the blocked map could remain in place for the 2022 elections.

Ultimately, though, Alabama enacted a map in time for this year’s elections that complies with the Voting Rights Act. And the Supreme Court ended up upholding Section 2 of the VRA.

As Louisiana voters await a resolution, voters in South Carolina remain in a similar predicament stemming from a lawsuit over a redrawn Republican-backed congressional map. The South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP sued the state in 2021 after the map was approved by the GOP-controlled Legislature, alleging an unconstitutional gerrymander in violation of the 14th and 15th Amendments.

The plaintiffs alleged that the map — which changed the composition of the state’s 1st and 6th congressional districts — was racially discriminatory because while it appeared to preserve Black voting strength in the 6th Congressional District, it weakened Black voters’ ability to influence elections in any of the other congressional districts by moving a “disproportionate number of white voters from the First and Second districts into the Sixth district.”

After the case went to trial in January of 2023, a three-judge panel struck down South Carolina’s 1st Congressional District, holding that “the movement of over 30,000 African Americans in a single county from Congressional District No. 1 to Congressional District No. 6 created a stark racial gerrymander of Charleston County,” which is geographically split between the 1st and 6th Congressional Districts.

Republican lawmakers appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court and asked for a reversal of the lower court decision. The Court agreed to take the case, and heard oral argument last October.

But months went by and a ruling never came. Then, in March of this year, the district court that rejected the map issued a decision allowing South Carolina to use it in the 2024 elections because “the present circumstances make it plainly impractical for the Court to adopt a remedial plan” in time for the June primary.

“Racial gerrymandering is something that courts have always struggled with,” Li told Democracy Docket. “Because the Supreme Court has created this weird binary that it can be race or it can be politics. And the reality is that a lot of times, it’s a little of both, especially in the South.”

Evans noted that, in the Louisiana case, the court ruled that the current approved map can’t go forward. He told Democracy Docket that there are seven different versions of congressional maps that the plaintiffs’ legal team submitted to the Legislature throughout the process.

Still, he’s optimistic that the high Court will resolve the case. “It’s always a roll of the dice when you go to the Supreme Court,” Evans said. “With that said, the court just ruled in the favor of Black voters less than a year ago in the Alabama case. So that gives us hope.”