2020 Redistricting Cycle Report: How Maps Were Challenged in Court

Every 10 years, the U.S. Census Bureau releases updated demographic data, prompting the reconfiguration of political districts. In April 2021, the Census Bureau published its state-level results that determined the reapportionment of U.S. House of Representatives seats, followed by more detailed demographic data in August 2021. This kicked off the decennial redistricting process and brought a deluge of redistricting litigation.

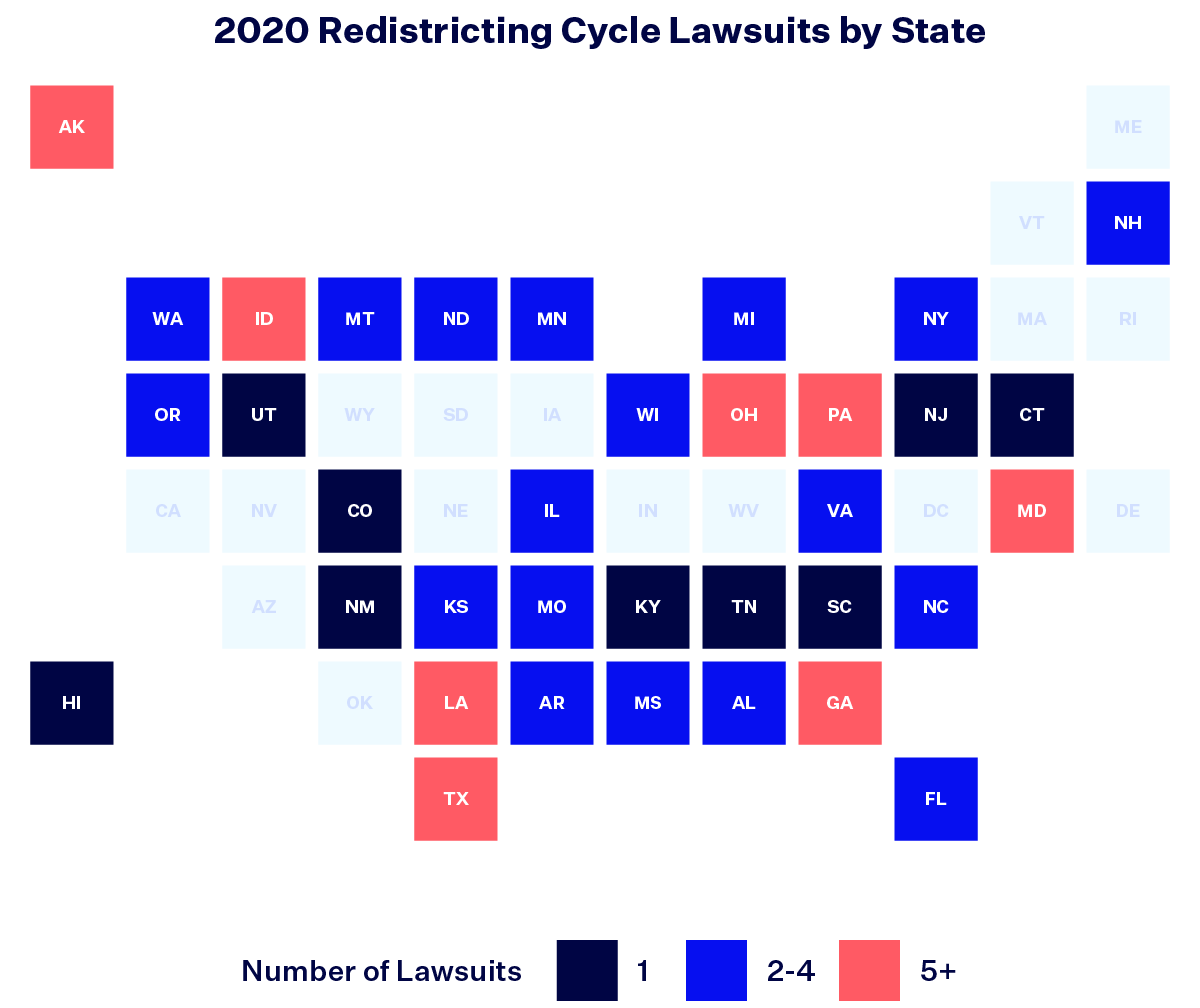

Since the release of 2020 census data, Democracy Docket tracked 111 lawsuits challenging maps (or lack thereof) related to 2020 redistricting. Of these 111 cases:

- 22 impasse lawsuits were filed when states failed to timely enact new maps,

- 87 lawsuits challenged enacted maps drawn with 2020 census data for a variety of reasons and

- Two lawsuits from Virginia dealt with an election held under outdated maps.

New Democracy Docket analysis of our dataset reveals the importance of redrawing political district lines and explores the ways that maps can be challenged and changed via courts. Our dataset focuses only on litigation over congressional or legislative (state House and state Senate) maps, though redistricting also takes place in other jurisdictions, such as city councils. The dataset includes all litigation in Democracy Docket’s database filed after the release of 2020 census data in April 2021 through Dec. 31, 2022.

Two-thirds of all states saw litigation over their maps drawn with 2020 census data.

Once a map is in place — whether enacted by a legislature, approved by a commission or drawn by a court-appointed expert — it can be challenged in court for violating state or federal law. We focus on redistricting lawsuits that challenge a state’s congressional map, state House map, state Senate map or some combination of all three.

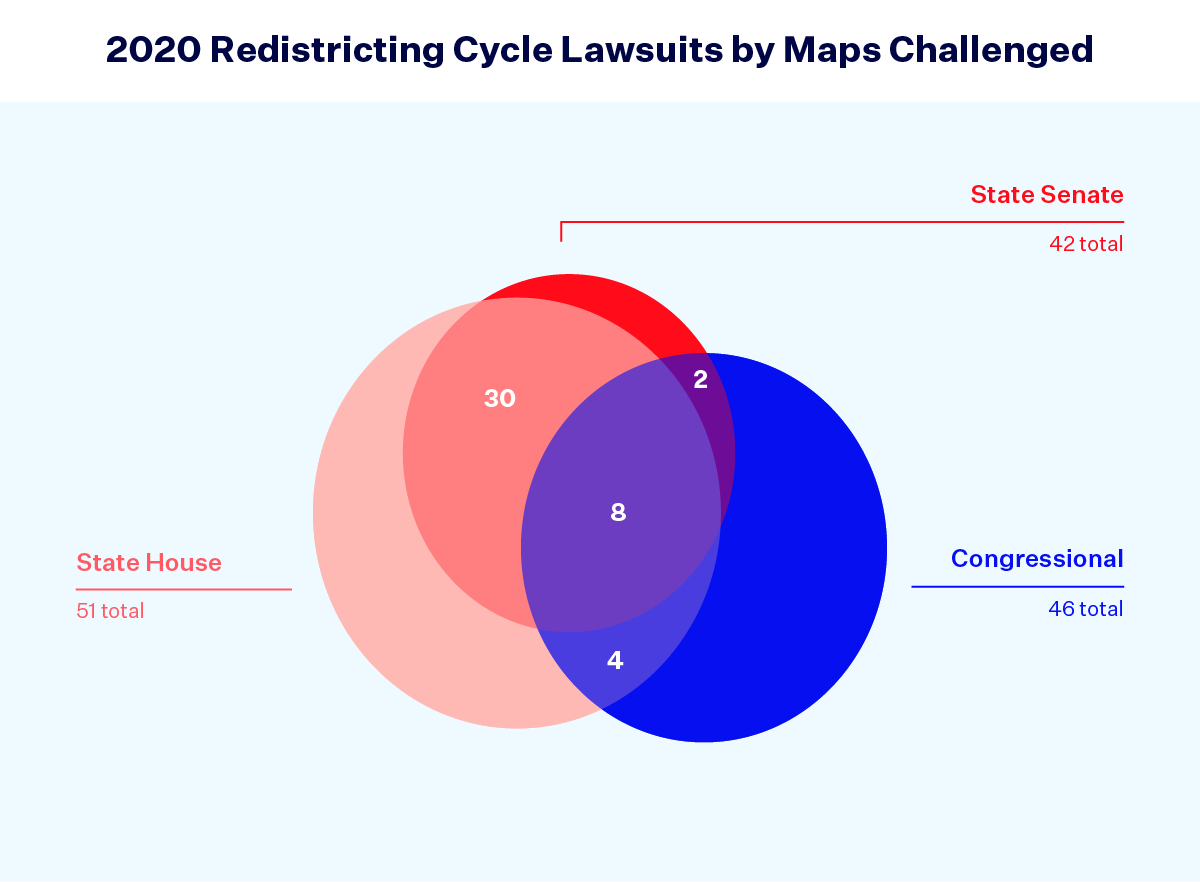

There were 87 total lawsuits that challenged congressional and/or state legislative maps drawn with 2020 census data, 46 of which included challenges to congressional maps and 55 of which included challenges to legislative maps (state House and/or Senate). This figure excludes the 22 impasse cases and two Virginia election cases.

Forty-six lawsuits challenged congressional maps.

There were a total of 46 lawsuits challenging congressional maps across 22 states, with 32 of these lawsuits focused solely on challenging a state’s congressional map. The remaining 14 lawsuits challenged the congressional map as well as some combination of state legislative maps.

Lawsuits against congressional maps have important implications that stretch beyond a state’s borders by influencing the partisan composition of the U.S. House of Representatives. In close national elections like the 2022 midterm elections, the outcome of litigation can have a huge impact on the final results. As we previously wrote, the decisions of courts in redistricting litigation contributed to the Republican Party’s current margin in the U.S. House.

Starting off the new year, nearly 70% of congressional lawsuits (32 out of 46) remain active and ongoing across 15 states. This includes states like New York and Texas, responsible for 26 and 38 congressional seats, respectively, as well as crucial battleground states like Georgia, home to 14 congressional districts. Many of the ongoing lawsuits have yet to reach the trial stage, the first step in the legal process. Coupled with the possibility of appeals and mandatory U.S. Supreme Court review in many redistricting cases, maps in these states could change from the maps used in the 2022 midterm elections.

Fifty-five lawsuits challenged state legislative maps.

Similarly, lawsuits challenging state House and Senate maps were filed in 23 states. Nine lawsuits challenged only a state House map, two challenged only a state Senate map and 30 lawsuits challenged both legislative maps. Including lawsuits that also challenged congressional maps (14), a total of 55 lawsuits challenged state legislative maps in 23 states. Of these 55 lawsuits, 58% (32 lawsuits) remain active and ongoing in 16 states.

As congressional maps do for the U.S. House of Representatives, state legislative maps determine the balance of power in state legislatures and can have a huge impact on state-level policy. Who controls the state legislature determines policies like ease of voting, access to reproductive health care and other crucial rights.

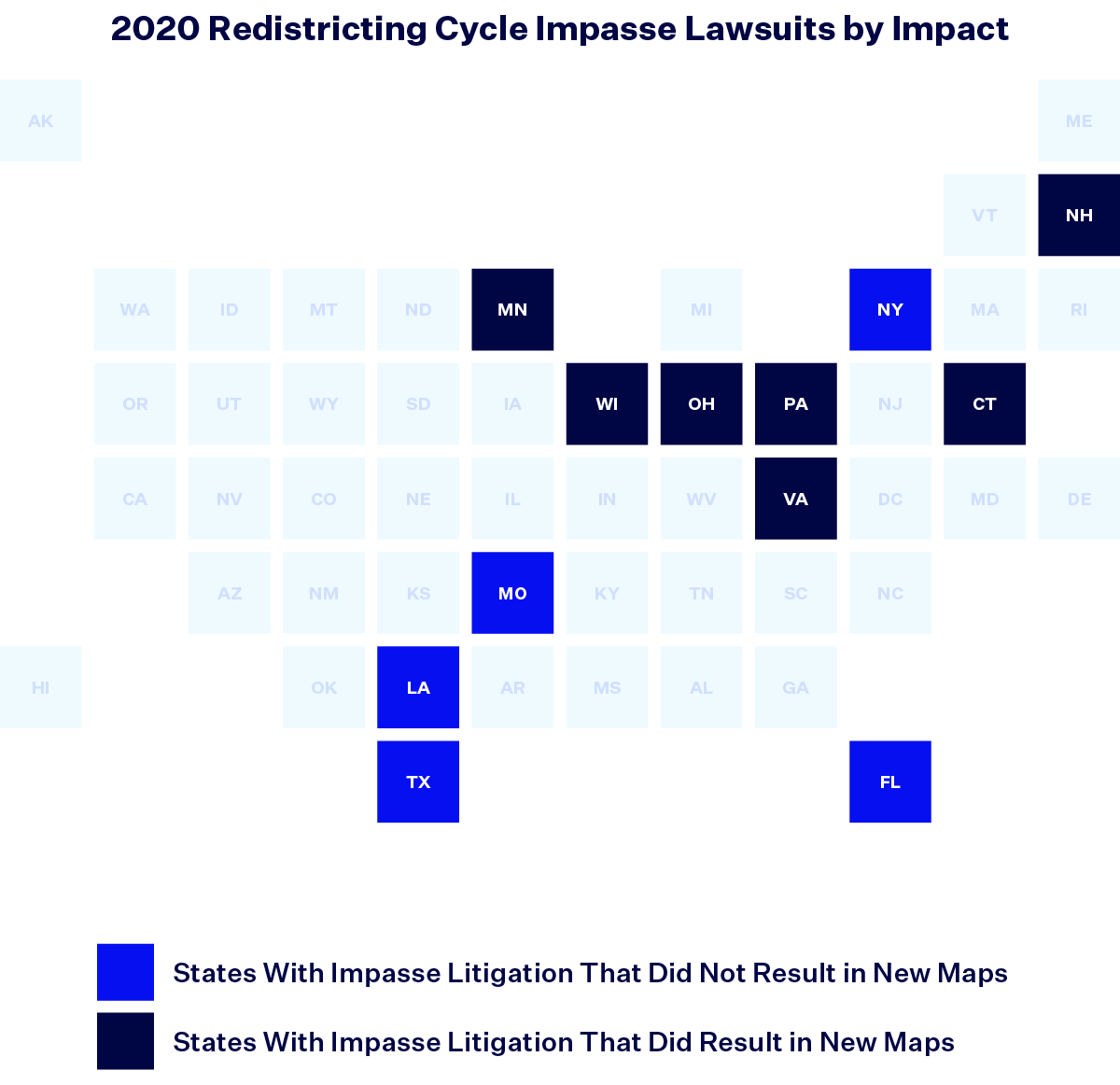

In seven states, courts imposed new maps after the redistricting process stalled.

One special category of redistricting litigation we saw in many states were impasse lawsuits. Impasse lawsuits occur when the entities normally tasked with drawing new maps, like the governor and legislature, fail to do so. This often happens in states where the legislature is controlled by a different party than the governor and the two can’t agree on a proposal. In these cases, an impasse lawsuit asks a court to step in and draw the maps instead. However, this redistricting cycle also saw impasse lawsuits in states like New Hampshire and Missouri where Republicans held full control of the redistricting process but failed to agree among themselves, at least for a little while.

In total, this redistricting cycle saw 22 impasse lawsuits across 12 states — some states had multiple lawsuits that were filed by different sets of plaintiffs or had lawsuits in different courts. Of these lawsuits, over 63% (14) solely involved a state’s congressional map. The remainder involved either a state’s legislative maps or both the state’s congressional and legislative maps.

Not all of these lawsuits successfully led to new maps being adopted; sometimes, the original map drawers ended up reaching an agreement outside of court. Ultimately, six states adopted new maps as a result of impasse lawsuits:

- Connecticut (congressional map),

- Minnesota (congressional, state House and state Senate maps),

- New Hampshire (congressional map),

- Pennsylvania (congressional map),

- Virginia (congressional, state House and state Senate maps) and

- Wisconsin (congressional, state House and state Senate maps).

A seventh impasse lawsuit in Ohio led to the adoption of interim state House and state Senate maps for the 2022 elections only thanks to the Ohio Redistricting Commission’s failure to comply with Ohio Supreme Court rulings.

Minnesota is perhaps the quintessential example of an impasse state. Courts have had to draw new districts every redistricting cycle since 1980 and this cycle was no different. After the Minnesota Legislature, with the state House controlled by the Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party and the state Senate controlled by the Republican Party, failed to reach an agreement on districts, a special panel appointed by the state Supreme Court released new maps on Feb. 15, 2022. The panel redrew districts using a least-change approach, adjusting the districts as necessary to reflect population changes while adhering to politically neutral redistricting criteria.

After the 2020 census, congressional and legislative maps were challenged in an overwhelming majority of states.

As this first set of data explains, redistricting does not end when maps are drawn nor when gridlocked states fail to pass new congressional or state legislative maps. With the U.S. House of Representatives and state legislatures hanging in the balance, we saw litigation in two-thirds of states following the release of 2020 census data. Fifty-five lawsuits challenged state legislative maps while 46 lawsuits challenged congressional maps. Impasse lawsuits were critical for the imposition of congressional maps in six states that accounted for 51 congressional districts. As we enter 2023, litigation will continue in a critical mass of lawsuits challenging both legislative and congressional districts across 20 states. The answer as to why maps are subject to litigation is best described by the data below.

Most redistricting lawsuits focused on partisan or racial unfairness.

One way map drawers manipulate district lines to produce certain electoral outcomes is to use partisanship to sort voters and draw maps to favor one political party over another; a second way is to rely on race to draw maps that diminish the voting strength of a certain racial group or groups.

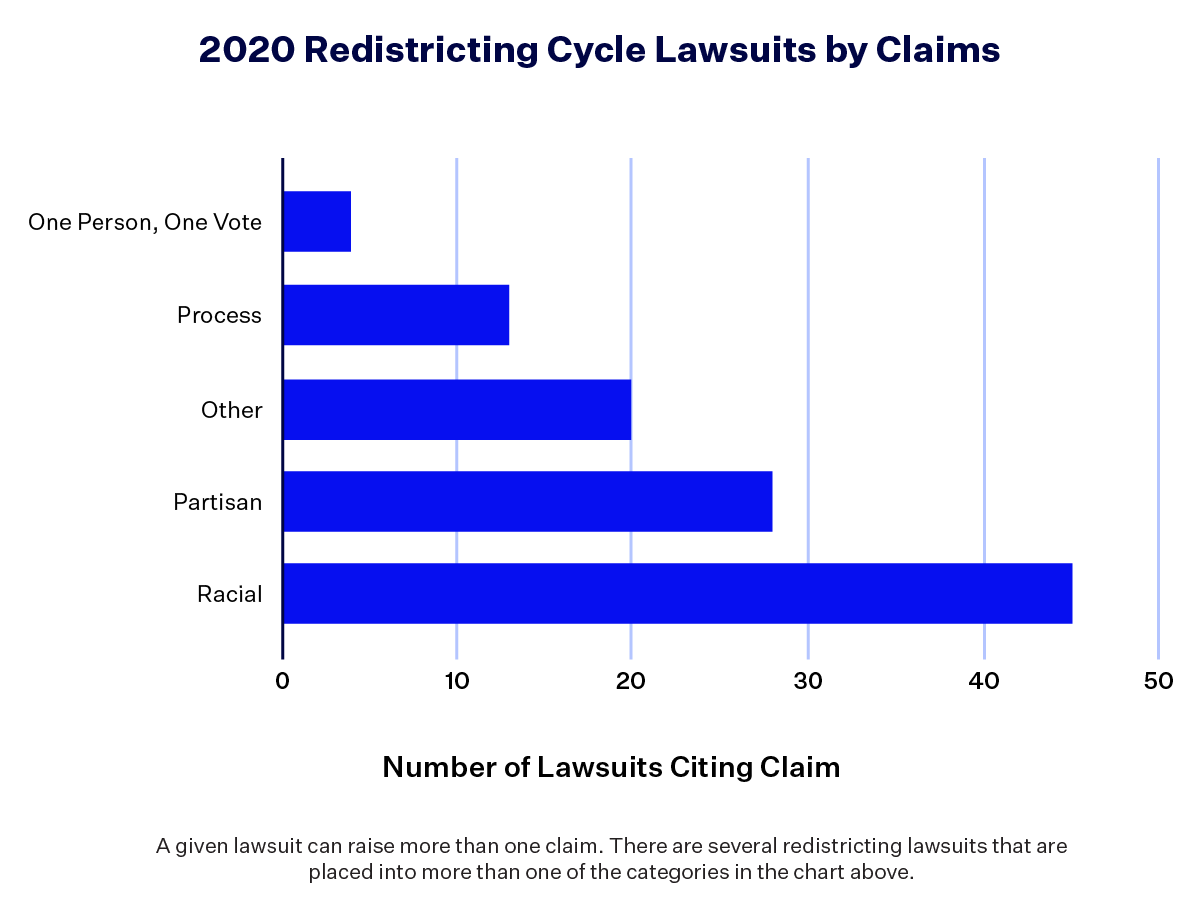

The largest portion of the lawsuits challenging 2020 census data maps focused on this racial or partisan activity, with 52% of the lawsuits challenging maps for racial reasons and 32% of the lawsuits challenging maps for partisan reasons. While most redistricting lawsuits brought partisan and/or racial claims against new maps, other state law or constitutional violations were also raised. (Any given lawsuit can bring multiple types of claims.)

Texas and Ohio saw the highest number of racial and partisan lawsuits.

Regarding racial claims, the states with the highest number of lawsuits were predominantly in the South. Texas led with eight lawsuits alleging that the Lone Star State’s maps are racially discriminatory, followed by Georgia (5), Alabama (4), Arkansas (3), Illinois (3) and Louisiana (3).

Among lawsuits challenging maps for partisan reasons, Ohio faced the most lawsuits (7). The other most litigious states for partisan gerrymandering claims included Maryland (4), Kansas (3), North Carolina (3) and Oregon (3). This reveals the limited overlap between racial and partisan claims, as only five lawsuits in the dataset asserted both claims at the same time; lawsuits claiming improper use of both race and partisanship occurred in Florida, Kansas (two lawsuits), North Carolina and Pennsylvania.

There were 45 lawsuits that challenged maps on racial grounds.

There are three main claims made against racially discriminatory maps: racial gerrymandering, racial vote dilution or state constitutional protections against the improper use of race when drawing districts.

Racial gerrymandering claims are rooted in the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment, which mandates that a state must treat individuals the same under its laws. In Shaw v. Reno (1993), the U.S. Supreme Court held that race cannot be the predominant factor in placing voters in certain districts, except if it is narrowly tailored to serve a compelling reason (in legal lingo, strict scrutiny).

In the 2020 redistricting cycle, 25 lawsuits raised racial gerrymandering claims. However, history, demographics and other state-specific factors greatly influence what racial groups are disadvantaged by improper redistricting. In large swaths of the country, including the Deep South, lawsuits alleged that mapmakers unduly used race to harm Black voters. In Alaska and North Dakota, the alleged improper use of race involved Native American or Alaska Native tribes. In Texas, several lawsuits alleged racial gerrymandering of Latino voters.

Common Cause v. Raffensperger argued that the Republican-controlled Georgia General Assembly used race as the predominant factor in drawing the 6th, 13th and 14th Congressional Districts. “The goal and effect of these unlawful tactics is to maintain the voting power of white voters, with the consequence that Black voters and other voters of color are unable to elect their candidates of choice,” the complaint reads, adding that lawmakers used race to sort voters into certain districts without any compelling state reason nor to comply with the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA).

Though the two concepts often get confused, racial gerrymandering is distinct from racial vote dilution, a claim brought under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA). Section 2 outlaws any voting law or district map that results in the “denial or abridgement of the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color.” In redistricting, this provision protects against racial vote dilution, which is when a state’s minority voters cannot elect the candidates of their choice. This often occurs when map drawers “pack” the voters into one district and “crack” them among other districts in order to weaken their collective voting power across a state. For the past 40 years, courts have relied on a test established in a 1986 case, Thornburg v. Gingles, to prove a pattern of racial vote dilution. One way to win a Section 2 racial vote dilution claim is to prove discriminatory intent on behalf of map drawers. However, and importantly, a plaintiff does not necessarily need to show discriminatory intent, but simply that the result dilutes minority voting strength. A pending U.S. Supreme Court case out of Alabama, Merrill v. Milligan, threatens the future application of Section 2.

Depending on the context, racial gerrymandering and racial vote dilution claims can be brought separately or together. There were 32 lawsuits challenging maps for racial vote dilution this redistricting cycle, 19 of which also asserted racial gerrymandering claims. When the Supreme Court decides Merrill later this spring, this interaction may only get more complicated.

In Louisiana, the 2021 map-drawing process was controlled by the Republican Legislature, which overrode a veto from Democratic Gov. John Bel Edwards (D) to pass a congressional map that maintains the (unfair) status quo. Black residents of Louisiana compose over 33% of the total population and 31% of the voting age population and vote cohesively as a bloc but, under the enacted map, can only elect the candidate of their choice in a single majority-minority district that snakes between New Orleans and Baton Rouge. It’s one of the state’s six congressional districts.

Consequently, in Ardoin v. Robinson, a group of voters and civil rights organizations argued that the adopted congressional map dilutes the voting strength of Black voters in violation of Section 2 of the VRA. In June 2022, a federal judge found that the map likely violates the VRA, but instead of redrawing a fair map as ordered, Louisiana Republicans filed an emergency application in the U.S. Supreme Court asking it to step in and reinstate the map. On June 28, 2022, the Court did just that. The decision in Merrill about Alabama’s map will likely determine the future of Louisiana’s map as well, with ramifications for fair representation for Black voters throughout the South.

Finally, race-based claims can be brought under state constitutions; nine lawsuits sought such relief. The lawsuits alleged that racial minority groups are protected under a different combination of state constitutional clauses such as equal protection, due process or free and equal elections. In Florida, a specific anti-gerrymandering amendment contains protections against diminishing the voting power of protected minority voters.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) hijacked the Sunshine State’s redistricting process in 2022. The Republican-controlled Legislature had passed its own map that appeared to comply with the state constitution, but after a gubernatorial veto, state lawmakers buckled under pressure from DeSantis. Ultimately, the Legislature approved DeSantis’ allegedly discriminatory map, which completely dismantled the 5th Congressional District, a Black-opportunity district that was previously represented by Rep. Al Lawson (D-Fla.).

Two lawsuits were filed against the map. Black Voters Matter v. Byrd specifically alleged that DeSantis’ map violates multiple provisions of the Fair Districts Amendment, a specific anti-gerrymandering measure adopted by voters in 2010. The state constitutional provision clearly states that “districts shall not be drawn with the intent or result of denying or abridging the equal opportunity of racial or language minorities to participate in the political process or to diminish their ability to elect representatives of their choice.” In May 2022, a trial court judge found that the map likely violated the Fair Districts Amendment “because it diminishes African Americans’ ability to elect candidates of their choice” in northern Florida. This decision was paused by appellate courts while litigation continues which meant that unfortunately, elections were held under the map during the 2022 midterms.

There were 28 lawsuits that challenged maps for partisan gerrymandering.

In the 2019 case Rucho v. Common Cause, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that it didn’t have the authority nor the ability to resolve partisan gerrymandering claims — when redistricting maps are drawn to favor one political party over another. “Our conclusion does not condone excessive partisan gerrymandering. Nor does our conclusion condemn complaints about districting to echo into a void,” wrote Chief Justice John Roberts in his majority opinion. “Provisions in state statutes and state constitutions can provide standards and guidance for state courts to apply.”

When Rucho closed the door on federal review of partisan gerrymandering claims, there remained optimism that state laws and state constitutions could provide important protections in this area. In this redistricting cycle, 28 lawsuits challenged maps for partisan gerrymandering in state court. Of these lawsuits, 26 challenged maps under state constitutions; only two (both in Oregon) challenged the same phenomenon solely under state law. Another Oregon lawsuit alleged both state law and state constitutional violations.

Of the 28 partisan gerrymandering lawsuits, 12 referred to specific redistricting provisions outlined in state laws or state constitutions. For example, the Ohio Constitution explicitly states that the “general assembly shall not pass a [congressional redistricting] plan that unduly favors or disfavors a political party or its incumbents.” In contrast, 15 of the lawsuits invoked a much broader protection, alleging that map drawers violated some version of free elections guarantees in state constitutions. (Of the 30 states that have a version of a free elections guarantee, 12 states have some form of constitutional requirement that elections be “free” and 18 states go even further, requiring that elections be “free” and “equal” or “open.”) One lawsuit in Michigan alleged that partisan gerrymandering violated both specific and broad provisions.

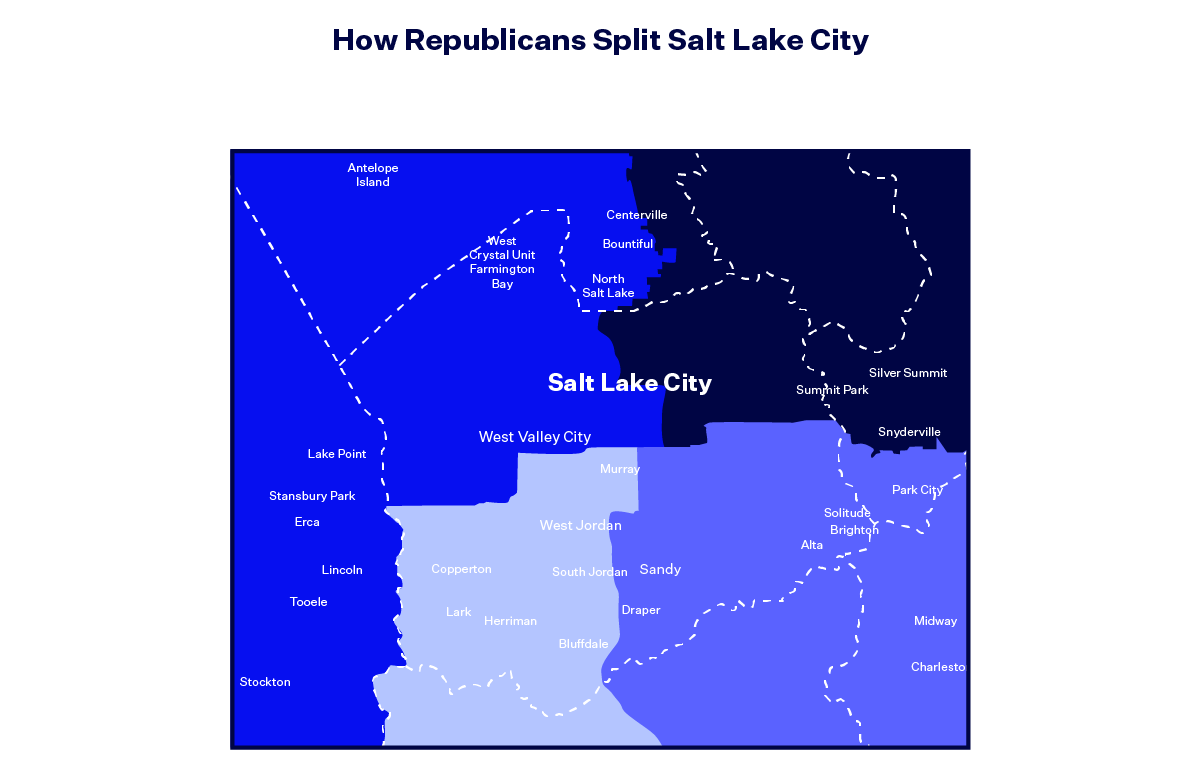

Salt Lake City is Utah’s most populous city and is demographically and culturally distinct from the rest of the state. Under redistricting standards that privilege communities of interest (groups of voters who have something in common) the sufficiently populous Salt Lake City would likely anchor its own congressional district. Yet, disregarding the advice of the state’s nonpartisan redistricting commission, the Republican Legislature enacted a map that divided Salt Lake City and Salt Lake County across all four of Utah’s congressional districts, ensuring that they all lean Republican.

Consequently, League of Women Voters of Utah v. Utah State Legislature argued that Utah’s congressional map drawn with 2020 census data is a partisan gerrymander that favors Republicans by “cracking” non-Republican voters across districts in violation of the Utah Constitution.

There were 33 lawsuits that cited a myriad of other claims.

There were 20 lawsuits that made legal claims over a range of other state law violations, often involving codified redistricting principles such as core retention, compactness, contiguity or preserving political subdivisions.

From requiring open meetings or failing to hold certain types of public hearings to not fulfilling statutory or constitutional duties or seeking automatic state court review, there are numerous ways that lawsuits can allege that legislatures or commissions made a process mistake in violation of state laws or state constitutions. There were 13 lawsuits alleging such process errors during the 2020 redistricting cycle.

The sole lawsuit brought in Hawaii, Hicks v. Hawaii Reapportionment Commission, challenged the state’s legislative maps. A group of voters argued that the new maps violate the Hawaii Constitution because 1) they fail to place state House districts “wholly” within state Senate districts when possible; 2) they fail to place state Senate districts “wholly” within congressional districts when possible and 3) the redistricting commission’s process was not independent and transparent. The first two claims deal with redistricting principles while the third claim is categorized as a “process” claim. The petition was ultimately denied by the state Supreme Court.

There were four lawsuits that challenged maps for violating the principle of “one person, one vote.”

A 1962 U.S. Supreme Court case invoked the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause to create the principle of “one person, one vote,” an expectation that districts contain roughly the same number of people. After the 2020 census, congressional districts average 761,000 people. (Congressional districts and state legislative districts are held to different standards of population equality, with legislative districts having a bit more leeway for not perfectly exact district populations.) When maps do not conform to the one person, one vote standard, they are malapportioned. Since population deviation is a fairly clear cut redistricting guideline to follow, only four lawsuits asserted that maps enacted with 2020 census data violated the one person, one vote principle; none succeeded on those claims.

It is important to note that impasse lawsuits — which we categorize differently from lawsuits challenging malapportioned enacted maps — cite the same argument under the 14th Amendment. The lack of a new map being enacted in a timely manner means that maps from the prior decade’s redistricting using out-of-date census data are in effect and are almost always malapportioned. Additionally, two Virginia lawsuits challenged the fact that the commonwealth held its 2021 Virginia House of Delegates elections under malapportioned maps enacted in the 2010 redistricting cycle.

Banerian v. Benson argued that the congressional map adopted by the Michigan Independent Citizens Redistricting Commission failed to comply with the constitutional requirement of one person, one vote. Based on Michigan’s population, commissioners were expected to draw districts that had a population as close to 775,179 people per district as possible. The complaint cited the fact that the adopted map’s largest congressional district has a population of 775,666 (487 above the ideal) and the smallest district has a population of 774,544 (635 below the ideal), a difference of 1,122 people. The lawsuit asked for the court to adopt a remedy map that had less significant population deviation, but this request was denied for the 2022 midterms.

The future of redistricting lawsuits challenging maps for racial unfairness remains uncertain.

Although litigation pertaining to maps drawn during the 2020 redistricting cycle raised a variety of claims, a majority of lawsuits centered on racial or partisan claims. Litigants across the country filed lawsuits alleging racial unfairness in the form of racial vote dilution, racial gerrymandering and other race-based violations. With the U.S. Supreme Court’s pending decision in Merrill v. Milligan, the future of certain racial claims — namely those brought under Section 2 the VRA alleging racial vote dilution — hangs in the balance. Meanwhile, plaintiffs on both sides of the political spectrum brought lawsuits challenging maps on the grounds of partisan unfairness, primarily raising claims under their state constitutions and state laws, with federal court review of partisan gerrymandering claims out of the question following the Supreme Court’s decision in Rucho v. Common Cause. Next, we turn to examining some of the outcomes of the lawsuits brought following the release of 2020 census data and how they impacted maps and voters across the country ahead of the 2022 midterm elections.

In six states, 16 lawsuits led to new maps for the 2022 elections.

Of all the lawsuits that challenged maps during the 2020 redistricting cycle, 16 led to a new map being used during the 2022 elections. These decisions affected maps in six states:

- Alaska (state House and Senate maps),

- Maryland (congressional map),

- New York (congressional and state Senate maps),

- North Carolina (congressional, state House and state Senate maps),

- Ohio (congressional, state House and state Senate maps) and

- Wisconsin (state House and Senate maps).

Most of these lawsuits resulted in redrawn maps due to partisan claims. Only the Wisconsin litigation led to a redraw based on racial claims after the U.S. Supreme Court found that the legislative maps adopted through the state’s impasse litigation improperly used race.

In Szeliga v. Lamone, two Republican members of the Maryland House of Delegates and Republican voters in Maryland challenged the state’s new congressional map. The plaintiffs argued that the originally enacted map drawn with 2020 census data was a partisan gerrymander that “cracks” and “packs” voters across the state, ignoring political boundaries and county lines to favor Democrats and dilute the voting strength of Republicans. They contended that, as a result, the map violated multiple provisions of the Maryland Constitution. Following a trial, the judge permanently blocked the map and ordered the General Assembly to draw a new map. After Gov. Larry Hogan (R) signed that new map into law, the plaintiffs and defendants agreed to dismiss the case.

Five states held their 2022 elections under maps found by a court to likely violate the law.

In total, five states (Alabama, Florida, Louisiana, Ohio and Tennessee) held 2022 elections under maps that at least one court found likely violated the law.

- Alabama (congressional map),

- Florida (congressional map),

- Louisiana (congressional map)

- Ohio (congressional and legislative maps) and

- Tennessee (state Senate map).

Maps in Alabama, Florida, Louisiana and Tennessee were deemed illegal by a lower court and temporarily blocked for the 2022 elections to allow time for the court to fully weigh the merits of the case. Then, on appeal a higher court reinstated the likely illegal maps solely for the 2022 elections, meaning that the challenged maps are still subject to change for future elections.

Ohio also held its congressional and legislative elections under unconstitutional maps after map drawers repeatedly failed to comply with rulings of the state Supreme Court but ran out the clock before the midterms, forcing the use of maps explicitly found to violate the state constitution.

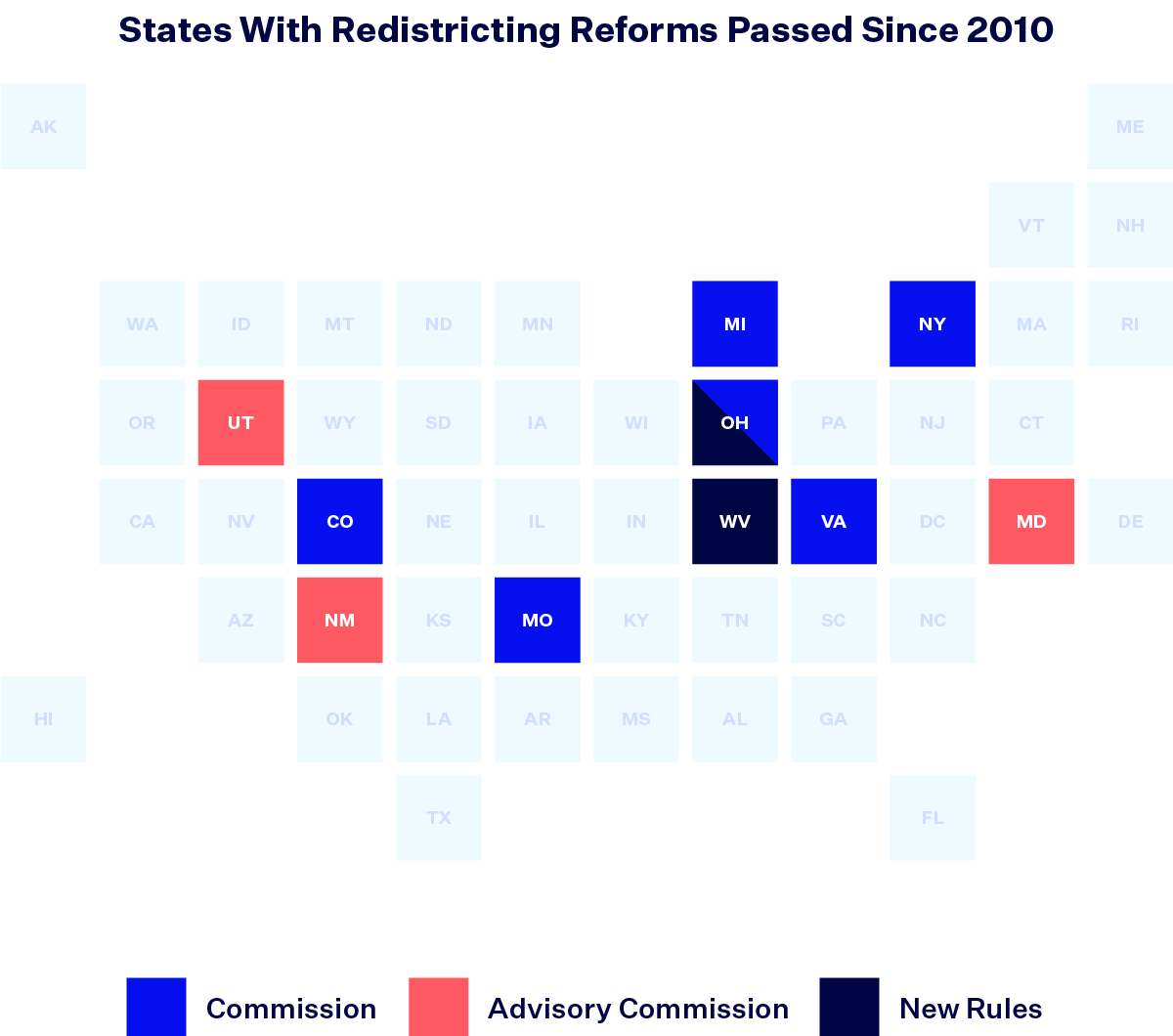

Ten states put new redistricting reforms to the test for the first time, but results were mixed.

The process states use to redraw districts isn’t set in stone; it can change between redistricting cycles in a variety of ways. With increased attention on partisan gerrymandering in recent years, many states adopted reforms to their redistricting processes to take the map-drawing pen out of the hands of politicians and give it to nonpartisan or bipartisan commissions. Other states adopted new rules for redistricting to keep lawmakers from relying too much on partisan considerations.

The most robust reforms were the adoption of an independent commission to draw maps instead of the state legislature. Colorado, Michigan, New York and Virginia all adopted commissions to draw all three of their maps. Missouri adopted two separate commissions to redraw state House and Senate districts, while Ohio empowered a commission to redraw state House and Senate districts and to draw the congressional map if the state Legislature failed to do so.

Some states adopted advisory commissions. These commissions merely offered proposed maps to state legislatures, which were largely free to ignore their suggestions. This is exactly what happened in Maryland, New Mexico and Utah: Advisory commissions offered proposals that each respective legislature ignored. In Utah, this occurred after the Legislature passed a law that reduced the commission reform previously passed by voters to merely an advisory role.

Ohio’s reforms also added strict rules to guide the map-drawing process, including standards for partisan fairness. West Virginia, rather than significantly overhauling the process used to draw maps, opted to divide its House of Delegates into 100 single-member districts rather than the 67 multimember districts used previously.

While 10 states enacted reforms since the 2010 redistricting cycle, these changes had significant impacts on the redistricting process in only six states — Colorado, Michigan, Missouri, New York, Ohio and Virginia — but not always in ways that the reformers intended. The New York and Virginia commissions failed to pass maps entirely, leading the Legislature in New York and the state Supreme Court in Virginia to step in and draw maps instead. This move in New York led to four lawsuits over maps, two of which are still ongoing as of Jan. 1, 2023. But nowhere did reforms fail quite as spectacularly as in Ohio.

Ohio’s redistricting reforms were adopted by voters in 2015 and 2018 and empowered a commission to redraw the state legislative maps and serve as a backup for the congressional map if the Legislature failed to pass a map. The amendments also included strict rules regarding partisan gerrymandering and designated the Ohio Supreme Court as the forum for any litigation challenging the maps.

After the Ohio Redistricting Commission and Ohio Legislature passed a first set of legislative and congressional maps that failed to comply with the partisan gerrymandering rules, the Ohio Supreme Court overturned the maps for violating the amendments. The commission reconvened to draw new maps, but continued to approve maps that the state Supreme Court found violated the state constitution. As a result, Ohio held its elections in 2022 under maps that violated the state constitution, according to the Ohio Supreme Court.

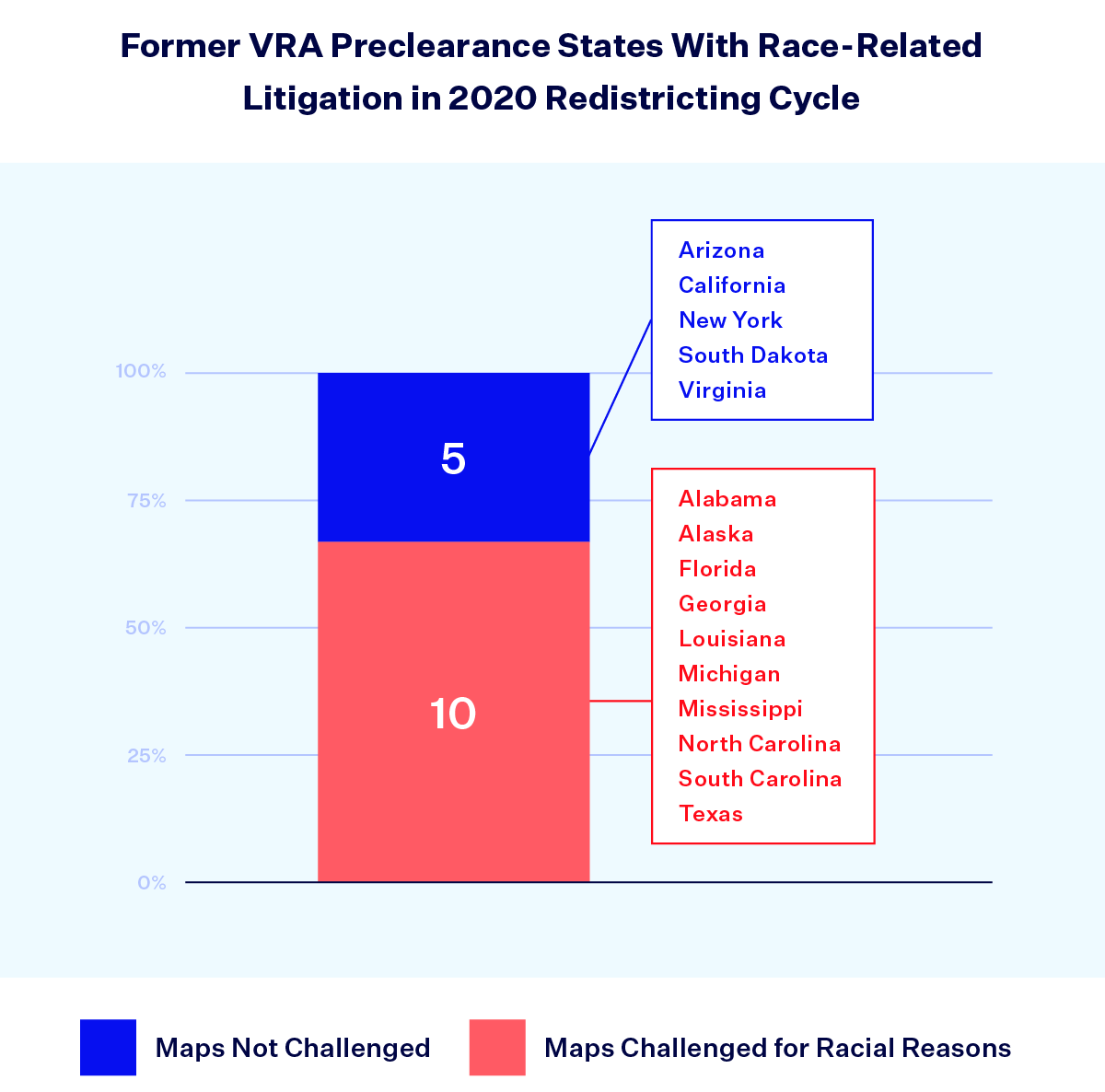

Of the 15 states no longer subjected to preclearance, 10 saw lawsuits challenging their maps on racial grounds.

Another major change to the redistricting process stemmed from the 2013 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Shelby County v. Holder. Prior to Shelby County, many states and counties with a history of racial discrimination were subjected to a preclearance process under Section 5 of the VRA, whereby any new redistricting plan had to be approved by either a federal court or the U.S. Department of Justice before taking effect. The Court’s ruling in Shelby County, however, invalidated the formula used to determine which states qualified for preclearance. As a result, this redistricting cycle was the first time no state had to get preclearance to enact new maps.

When Shelby County was released in 2013, nine states were subject to Section 5 preclearance in their entirety: Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, Texas and Virginia. Individual counties or townships in California, Florida, Michigan, New York, North Carolina and South Dakota were also covered, which meant those states similarly had to seek preclearance for new redistricting plans. Section 5 of the VRA was thus a powerful tool reaching across 15 states.

Thanks to the ruling, these 15 states no longer needed federal approval to implement new maps following the release of 2020 census data. Ten of these states — Alabama, Alaska, Florida, Louisiana, Georgia, Michigan, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina and Texas — all saw lawsuits that challenged their new maps based on the kind of racial claims that Section 5 preclearance was intended to safeguard against.

In fact, of the 45 lawsuits that challenged maps on racial grounds, over two-thirds (31) were in states that used to be subject to preclearance. While not all of these lawsuits did or will successfully find a racial violation and not all of these lawsuits would have been prevented by preclearance, the sheer volume of cases from previously precleared states indicates the ramifications of the 2013 decision in Shelby County. All evidence suggests that many of these states haven’t changed their behaviors when it comes to redistricting and continue to draw electoral districts in a discriminatory manner.

Prior to 2013, South Carolina was required to get preclearance for new state House, state Senate and congressional maps. As a result of Shelby County, this redistricting cycle was the first time since 1965 that the state had free rein to redraw districts without federal oversight. After the South Carolina Legislature enacted new maps, the plaintiffs in South Carolina NAACP v. Alexander contended that the state House and congressional map were racially gerrymandered in violation of the 14th and 15th Amendments.

2023 kicked off with 55 active redistricting lawsuits and two crucial cases before the U.S. Supreme Court, so maps across the country are far from settled.

Although redistricting is often described as a “once every decade” process, that phrasing fails to capture the ongoing litigation that occurs after maps are enacted. The release of census data and reapportionment may happen once a decade, but the process of drawing and redrawing lines will continue throughout the following 10 years. To exemplify this phenomenon, there were 55 active and ongoing redistricting cases at the start of 2023.

In addition, two redistricting cases ended up on the U.S. Supreme Court’s docket for its 2021-2022 term: Merrill v. Milligan and Moore v. Harper. Merrill centers on whether the state of Alabama violated Section 2 of the VRA when it enacted a congressional map that created one rather than two majority-Black districts. Moore, which emerged from a redistricting case in North Carolina, gives the Court an opportunity to review a right-wing constitutional theory that would give state legislatures unchecked power over federal elections, which includes unfettered authority to enact unfair congressional maps. In both cases, oral arguments were held last fall and we can expect (potentially consequential) rulings before the Court recesses for the summer, usually around late June. As of Jan. 1, 2023, three other congressional redistricting cases (from Kansas, Ohio and Mississippi) have pending requests before the Supreme Court.

The fight for fair districts has played out in public hearings before state legislatures, advocacy campaigns for independent commissions and in courtrooms across the country. The 2020 redistricting cycle reveals a surge of litigation from all angles, illustrating how vital district lines are to politics, policy and representation.