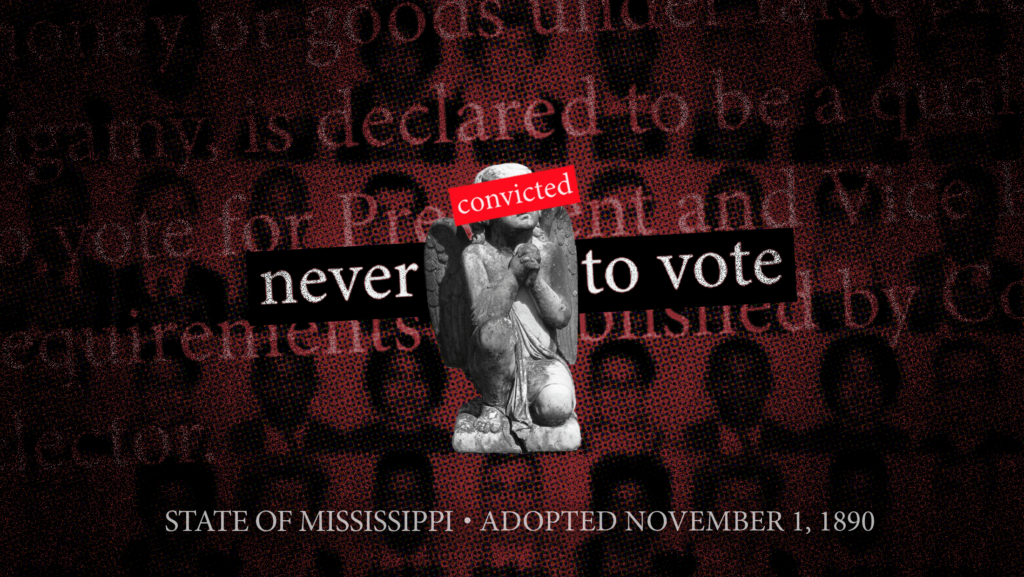

A Felon Can Run for President. In Mississippi, He Probably Can’t Vote.

In a legal challenge against Mississippi’s voting ban for people with certain felony convictions, even after they’ve completed their sentences, state officials in support of the law stressed that stripping away the voting rights of tens of thousands of Mississippians indefinitely was not a “punishment.”

But for some residents, the ban is an extension of the debt they feel they’ve already paid to society. “They convict us for the smallest things,” said Kynoa Trotter, 29, of Pike County. “And then we can’t vote, but we still gotta live in the meantime,” he said. “It ain’t like we can just disappear.”

One individual, 52, who has tried at least three times to get his voting rights restored, said he doesn’t feel like a true citizen. “I have children (an adult son and daughter) and I talk politics with them,” he said. “I encourage them to vote, but they’ve never been to the polls with their dad.”

The Mississippi resident, who requested anonymity to talk candidly about his conviction, told Democracy Docket he was a young man when he was found guilty of possession of stolen goods and attempted armed robbery in 1995. Nearly 30 years later, he feels he’s still paying for the crime.

The state sought to uphold Section 241 of the Mississippi Constitution, a Jim Crow-era provision opponents argue is cruel and unusual punishment under the U.S. Constitution. The secretary of state (R) has said the law isn’t punitive, and essentially allows Mississippi to regulate the “qualifications” of the electorate.

In July, the nation’s most conservative appeals court agreed. The 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that holding Section 241 as unconstitutional would impede the ability of the state Legislature and citizens “to determine their voting qualifications.” The court determined that “felon disenfranchisement is not a punishment, much less cruel or unusual.”

The decision means Mississippians who were convicted of a crime on the state’s list of disenfranchising offenses and who have not completed its voting restoration process will not be able to vote in this fall’s election. That includes the men who spoke to Democracy Docket. “I feel like a hypocrite,” Trotter said. “I can’t say nothing or have [an] opinion, because I’m not even voting.”

In response to the ruling, attorneys with the Southern Poverty Law Center, which represented the plaintiffs, said the decision “upholds a discriminatory lifetime voting ban on individuals, a majority who are Black and brown, who have already served their sentences.” The organization declined to say whether they’ll appeal.

Another attorney on the case, Jon Youngwood, said in a statement the team was “heartened by the opinion of the six dissenting judges.” In a searing rebuke, the judges wrote that voting is the “lifeblood of our democracy … These individuals, despite having satisfied their debt to society, are precluded from ever fully participating in civic life,” they wrote.

It’s the same sentiment felt by activists in the state who’ve lobbied for an end to the prohibition, with many citing the provision’s roots in the Jim Crow-era. Section 241 was enshrined in Mississippi’s 1890 constitution with the express purpose of denying Black men the right to vote.

“One of the most extraordinary and horrific successes of white supremacy is that we’ve bought into the lie that these voter qualifications are race-neutral,” said Paloma Wu, deputy director of impact litigation at the Mississippi Center for Justice. Wu likened the ban to the poll tax and literacy tests, both tools historically used to disenfranchise Black voters despite seeming race-neutral.

“We cannot have the fantasy that we’re doing meritocracy through democracy,” she said. “That is always going to be a fantasy.”

If a resident has completed their sentence and wishes to vote again, they can either get their record expunged or ask a lawmaker to sponsor a “suffrage” bill. The state constitution allows the Legislature to restore the right to vote to an individual disqualified because of a crime, but requires a two-thirds vote of both chambers.

The governor can sign the bill, return it to the Legislature with objections, veto it or leave it unsigned. If the governor hasn’t returned or taken action within five days after receiving the bill, it becomes law. But he isn’t required, nor is any lawmaker, to explain the reasoning behind his decision.

Hannah Williams, who helps run the suffrage application process at Mississippi Votes, a nonprofit that aims to bolster civic engagement in the state, said some people have been unsuccessful multiple times, but remain persistent despite having no guarantee that the bills will be approved. “It’s a gamble,” Williams said. “So we just tell them, ‘hold tight.’”

One positive development she’s seen, Williams said, is the number of lawmakers on both sides of the aisle who are willing to sponsor a suffrage bill. Of the 13 state legislators who sponsored bills in the past legislative session, three were Republicans. “There’ve been times where we’ve kind of been amazed that some folks submitted suffrage bills, because maybe they haven’t been [vocally] pro-voting rights restoration,” she said.

Nationally, research shows participating in the democratic process can help reduce recidivism rates, said Nicole Porter, the senior director of advocacy at the Sentencing Project.

“If the secretary of state or any other official cares about community safety,” she said, “they would be supportive of enfranchisement policies for people with felonies, including people completing their sentence inside of prisons and jails, because the data shows that voting is a series of prosocial behaviors that can help reduce [the likelihood that people will reoffend].”

Trotter was convicted of burglary in 2017, and of possessing a firearm as a convicted felon in 2019. He was discharged in 2020. His suffrage bill didn’t make it to a full vote in the House or Senate, nor did the other individual’s. Both men said they plan to try again.

“We got this guy running for president and he’s a convicted felon like me,” the individual said, referring to former President Donald Trump who was recently convicted of 34 felonies in New York. “It doesn’t make sense.”

Read the 5th Circuit decision here.