Barriers to the Ballot for Native Americans

Indigenous People’s Day is increasingly celebrated on the second Monday of October in states and cities across the nation. There are 574 federally recognized Indian tribes in the United States and approximately 9.7 million American Indians and Alaskan Natives according to the latest census data, likely a low estimate due to undercounting on reservations.

In today’s Data Dive, we examine the systemic issues hindering the political participation of Alaskan Native and American Indian voters. In 2020, the Native American Rights Fund (NARF) published “Obstacles at Every Turn: Barriers to Political Participation Faced by Native American Voters,” an in-depth report based on nine public hearings with over 120 individual testimonies. We’re taking a look at the report to highlight some illustrative evidence and summarize the key takeaways.

Here are the key takeaways:

There is a legacy of discrimination that continues today.

The report begins by chronicling the long, dark history of genocide, direct warfare and forced assimilation imposed on Indigenous peoples — first by European settlers who arrive on the continent around 500 years ago and later by federal and state governments of the United States. One of the most enduring and most recent tools of oppression has been exclusion from political participation. While the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act formally granted voting rights to all Native Americans, states continued to prevent these citizens from voting — de jure or de facto, and to differing extents — until the passage and enforcement of the Voting Rights Act (VRA) in 1965.

The harmful legacy of American Indian policy produces understandable antipathy and distrust among Native communities towards non-Native governments, impacting political engagement. According to a survey conducted with 2,800 voters in four states, Native voters have the most trust in their tribal governments. The federal government tops the list as the most trusted of non-tribal governments, compared to state and local. Only 5% of South Dakota respondents indicated they most trusted their local government, although it is local jurisdictions that often take the biggest role in election administration.

Native Americans are underrepresented in local election positions, such as town or county clerks or poll workers. The report tells the story of Stephanie Thompson, a member of the Lac du Flambeau Band of Chippewa Indians, who ran for town supervisor against a non-Native incumbent. Thompson and her supporters requested absentee ballots that never arrived, fielded unanswered calls to election officials and when they travelled to cast a ballot in-person, were belittled by a non-Native clerk who insisted they must have filled in their applications incorrectly. This example is illustrative of the distrust and discouragement that non-Natives foster when they exclude Native Americans from the elections that concern their very own communities. Additionally, according to the report, Native voters routinely find their voter registration applications rejected, registration status purged from the voter rolls, get turned away at the polls or their ballots go uncounted without an opportunity to cure mistakes.

As redistricting continues across the country, pay careful attention to how districts are drawn around tribal lands. Historically, states with significant Native populations have created maps that “pack” Native voters into one district to dilute their strength elsewhere or “crack” communities across several districts so they cannot gain a majority in any of them. These tactics violate the principle of one person, one vote and diminish Native representation.

Individuals in rural areas face intense geographic isolation and logistical challenges through every stage of the voting process.

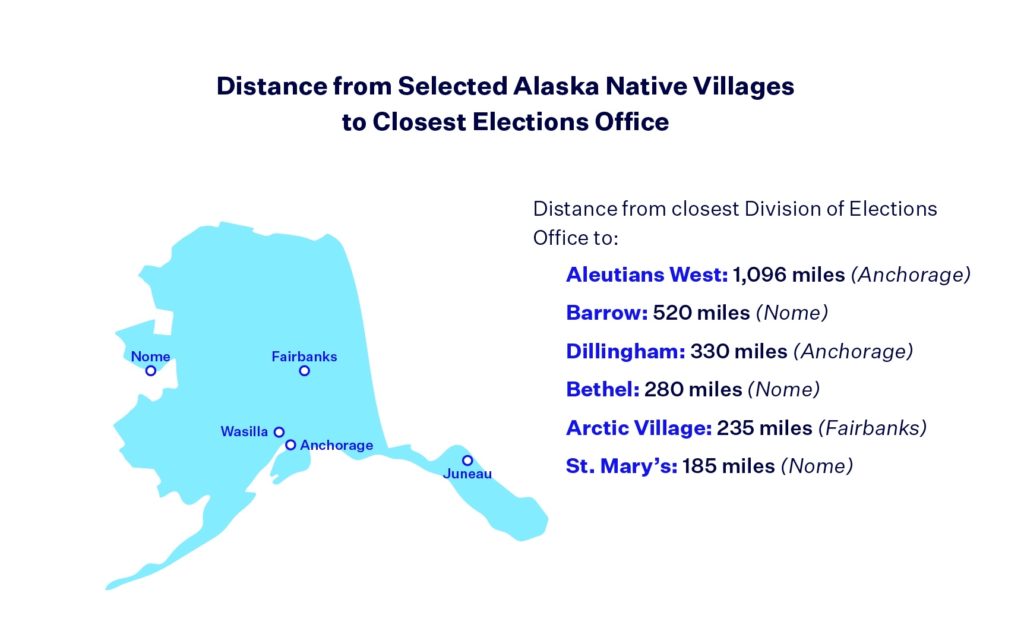

Native Americans reside in every region of the U.S., including major metropolitan areas, but the most exacerbated logistical barriers to voting are faced by residents on reservations or in other rural areas. In certain sparsely populated areas in Alaska, the closest election office can be hundreds of miles away and an expensive and time-consuming trip.

While Alaska presents the most extreme geography, the report also cites the geographic isolation and often insurmountable natural barriers in the Havasupai Indian Reservation located at the bottom of the Grand Canyon, the expansive and heavily wooded Colville Reservation in Washington and the extremely isolated Red Lake Indian Reservation in northwestern Minnesota, to name a few. Intuitively, these physical barriers impact access to in-person activities like voter registration and voting.

However, voting by mail is not the catch-all solution that one may assume (although precincts that fail to reach the population threshold for in-person polling places are sometimes designated as automatic, vote-by-mail areas instead, causing confusion). First, roads can be nonexistent or in poor conditions, making mail delivery slow or unreliable. Outside of the main metropolitan areas in Arizona, only 18% of Native American voters in that state have mail delivered to their home. Second, Native Americans in rural areas can have noncity-style mailing addresses which are instead based on highway numbers, PO boxes or solely descriptive. The report gives an example of what a non-city style address may look like: “the house located on the right side of BIA-41 between highway marker 17 and highway marker 18.” These nontraditional addresses pose issues for both voter registration and mail-in ballot delivery.

Poverty exacerbates every single logistical barrier.

The ease or difficulty with which someone can cast a ballot is labelled by political scientists as “the cost of the voting.” But, voting truly does have real, tangible costs — postage stamps, vehicle access and gas money, internet connectivity and importantly, time. Consequently, with the highest poverty rate of any population group at 27% — double the nationwide poverty rate — low socio-economic status makes casting a ballot an even costlier endeavor.

The Federal Trade Commission estimates that over 90% of tribal communities lack access to broadband Internet. High rates of homelessness and housing insecurity mean that many lack a reliable address for voter registration purposes or voting by mail, and constant moving makes casting an uncounted out-of-precinct ballot more likely. As a result, breaking this cycle of suppression and disadvantage through voting and increased political power still presents a dilemma. Yet, for Native Americans, “exercising their voting power can help them improve their: (1) socio-economic status, (2) self-determination, (3) land rights, (4) water rights and (5) health care, among other things,” the report argues. “Simply put, Native American political power improves their lives, the lives of their children and the American electorate in general.”

There are clear, reasonable policy solutions to help Native Americans overcome these barriers.

While the report details the breadth of challenges faced by Alaskan Native and American Indian voters, they are presented as issues that can be mitigated through thoughtful policy and sufficient political will. In fact, there are certain policies that we know specifically disadvantage Native voters: requiring IDs to vote in person without accepting tribal-issued IDs, banning community ballot collection and limiting translated voting materials or language assistance, to name a few. Native American activists and elected officials, and their allies, have been advocating for state and federal action on the matter of voting access for years. NARF’s report moves the policy conversation forward with important data.

In August, Reps. Sharice Davids (D-Kan.) and Tom Cole (R-Okla.) and Senator Ben Ray Luján (D-N.M.) introduced the Frank Harrison, Elizabeth Peratrovich and Miguel Trujillo Native American Voting Rights Act (NAVRA). NAVRA is endorsed by NARF and tackles several of the hardships outlined in the report by expanding access to in-person polling locations, permitting community ballot collection and the use of tribal-issued IDs for voter identification, allowing certain buildings to be designated for voter registration purposes in lieu of home addresses, creating a task force to improve voter outreach and education and more.

While NAVRA still awaits movement in the House, the bill has been added to the recently introduced John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, S.4, in the Senate. If enacted into law, NAVRA would improve voter access for many and take the first step to remedying a centuries-long injustice and exclusion from the democratic process.

Find more information on NARF’s report and how you can get involved here.