Friend or Foe: Analyzing Amicus Briefs in Alabama’s SCOTUS Case

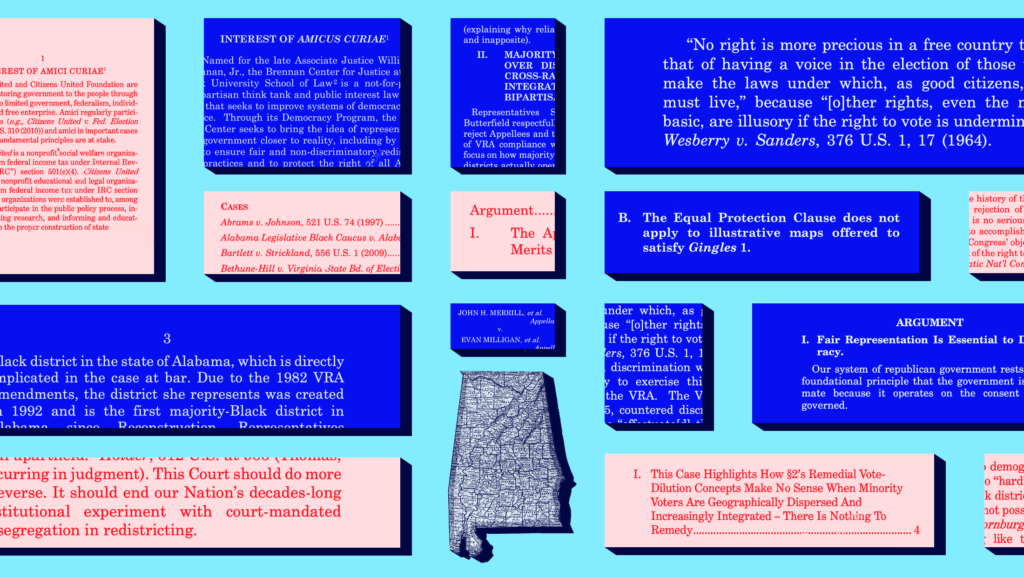

On the first Monday of October, the nation’s highest court opens its doors and begins holding oral arguments in the several dozen cases it has handpicked to hear. But, long before that happens, documents already filed in the U.S. Supreme Court’s pending lawsuits clue us into what’s at stake and, importantly, who’s on what side. Earlier this summer, amicus curiae briefs were due in Merrill v. Milligan, the upcoming case on whether Alabama’s congressional map violates Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA). Section 2 prohibits any law that has the intent or effect of abridging the right to vote “on account of race or color.”

Amicus curiae translates to “friend of the court.” These briefs are from individuals or organizations that are not parties in the case but have an interest in the outcome. They often present new data, potential ramifications and novel legal arguments. According to a law review article by U.S. Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-R.I.), the number of amicus briefs filed in the 2014 term (781) represented an increase of over 800% from the 1950s and an increase of 95% from 1995. In 2020, the number of submitted amici swelled to 940. “The increasing prevalence of amicus briefs correlates with a rise in the Supreme Court’s reliance on them,” writes Whitehouse, noting how amici citations in court opinions has also increased, before reaching another crucial conclusion: “The amicus brief is now a powerful lobbying tool for interest groups.”

In Merrill, a total of 36 amicus briefs were submitted — 13 in support of the state of Alabama, 22 in support of the plaintiffs who want a second majority-Black district under the VRA and one in support of neither party. It’s common for justices to adopt the language or legal arguments embedded in these influential documents in their final opinions. After reviewing all 36 amici, we’re highlighting just a handful of the most insightful, provocative or compelling briefs.

Here are some briefs in support of the state of Alabama.

In January 2022, a lower federal court found that Alabama’s congressional map likely violated Section 2 of the VRA and ordered the Legislature to redraw a VRA-compliant map with a second majority-Black district. The state of Alabama rushed the case to the Supreme Court, which paused the lower court’s decision on its shadow docket before adding the case to its merits docket.

Now, the state of Alabama wants the Supreme Court to adopt a “race-neutral” approach to redistricting that would effectively eliminate the power behind Section 2. Under Alabama’s preferred solution, Section 2’s protections against minority vote dilution would be rendered useless. Some of the groups and individuals who submitted briefs in support of the state of Alabama include the state of Louisiana (which has an open case on similar claims), the Republican National Committee, the chair of the Alabama State Republican Executive Committee, the National Republican Redistricting Trust, the American Legislative Exchange Council and the Public Interest Legal Fund.

Below are some notable arguments raised by supporters of Alabama’s position.

America First Legal

America First Legal is a conservative legal group led by senior members of former President Donald Trump’s administration, including senior advisor to the president Stephen Miller and chief of staff Mark Meadows. In its brief, the group presents a revisionist history of Section 2 of the VRA, differentiating between an “original Section 2” and a “new Section 2.”

“That original Section 2 prohibited intentional denials of the right to vote on account of race, just like the Fifteenth Amendment,” reads the amicus brief. “The claims here are under a much different Section 2, enacted in 1982 as a congressional attempt to override this Court’s holding that Section 2, like the Fifteenth Amendment, requires a showing of purposeful discrimination.” The phrase “this Court’s holding” refers to a 1980 case where the Supreme Court held that Section 2 does not afford any additional protections beyond the 15th Amendment. Just two years later, Congress amended the VRA, as is permitted in its purview, changing the language in Section 2 to state that unlawful results, and not just unlawful intent, can impermissibly abridge the right to vote. America First Legal takes issue with this 1982 addition of a results test into the VRA.

To be clear, the “new” Section 2 was enacted in 1982 and has been operational for the past 40 years, including in the context of redistricting. But, this Trump official-led group wants the Court to “do more than reverse” the lower court’s decision and declare Section 2 unconstitutional.

Five of the seven U.S. House members from Alabama

Five Republican members of Congress representing Alabama submitted an amicus brief that fervently argues that Section 2 does not require proportional representation (the idea that the percentage of voters of a certain race or party should translate directly to the percentage of seats those voters win). Here’s the catch — no one is arguing that Section 2 requires proportionality.

Instead, the amicus brief emphasizes the importance of core retention, a redistricting principle that promotes preserving districts as they were drawn in previous decades. These five white members of Congress emphasize that this principle is “race neutral,” ignoring the possibility that the districts drawn by the Alabama Legislature in 1992, 2002 or 2011 were created in an environment that was far from racially neutral. Core retention also helps incumbents ensure that they have a smoother path to re-election, so it’s unsurprising that five incumbents prioritize this principle. (The only GOP U.S. House member from Alabama who did not join this brief ran for a statewide position, so he is no longer an incumbent.)

Other highlights:

- The Project on Fair Representation, a legal defense group that fights initiatives or laws that advance opportunities for non-white people (led by Edward Blum, the non-lawyer activist behind Shelby County v. Holder), submitted a brief that argues that Section 2 is about voting access and not redistricting. “Redistricting decisions, however, affect no one’s right to cast a vote, but only the geographic, demographic, and political context in which that vote is counted,” writes the organization.

- Citizens’ United — yes, that opening-the-campaign-finance-floodgates Citizens’ United — submitted a brief that argues that Alabama is “increasingly integrated” so there is no issue at hand to remedy. (At the trial level, federal judges determined that Alabama’s Black population is indeed “sufficiently large and geographically compact” enough to constitute a second majority-Black district.)

Here are some briefs in support of the Milligan plaintiffs.

The Milligan plaintiffs argue that Alabama is violating Section 2 by failing to draw a second majority-Black congressional district. Some of the groups and individuals who submitted briefs in support of this position include the American Bar Association, a bipartisan group of senators — including current Sens. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.), Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) and Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) — Harvard professors, three Republican former governors, Washington, D.C. and 20 other states, civil rights advocacy groups — such as Campaign Legal Center, Brennan Center for Justice, Southern Poverty Law Center and Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights — and a group of city and county governments.

Below are some notable arguments raised by parties who support Section 2 of the VRA and its application in this Alabama case.

U.S. Department of Justice

The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) submitted an amicus brief in support of the Milligan parties. The DOJ’s position is clear and unequivocal, but focuses on many technical legalities surrounding Section 2. The DOJ clarifies that Section 2 does not establish a right to proportional representation, as some of the opposing amicus briefs suggest.

In refuting the opposing parties’ argument that Section 2 impermissibly uses race, the DOJ writes: “Section 2 is self-limiting: It authorizes race-conscious districting remedies only if and to the extent required to respond to the ‘regrettable reality’ of racially dominated politics.” Alabama happens to be an undisputedly racially polarized environment, meaning “Black voters have no meaningful chance of electing their preferred candidates unless they constitute a majority or near-majority in a district.”

At another point, the DOJ calls Section 2 “one of the most effective prohibitions on discrimination in voting that Congress has ever enacted.”

U.S. Rep. Terri Sewell (D-Ala.)

In contrast to the brief submitted by the collection of GOP members of Congress representing Alabama, the lone Democrat in the House delegation, U.S. Rep. Terri Sewell (D-Ala.), also filed an amicus brief. Sewell, who represents Alabama’s sole majority-Black district, writes alongside several other Black House members. Since 1819, of the 188 members of the U.S. House ever elected from Alabama, only six have been Black, including Sewell. “Over time—in big ways and small—the representation, mutual respect, and dialogue fostered by majority-minority districts can lead to meaningful communication, awareness, and changes in perspective in Congress and beyond,” describes the brief submitted by Sewell, along with Reps. Joyce Beatty (D-Ohio), G. K. Butterfield (D-N.C.) and Gregory Meeks (D-N.Y.).

“All told, in the fifty-six years since it was enacted, Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act has helped the United States make significant strides towards a more representative and integrated society,” the brief concludes. “The creation and continuation of majority-minority and crossover districts are essential to this progress.”

Alabama historians

A group of historians and scholars who specialize in Alabama history wrote a brief that negates the selective history put forward by the state of Alabama. The historians instead outline how the Black Belt — a region named for its rich, fertile soil that runs through the center of the state — is a community of interest. Understanding the history and composition of Alabama’s Black Belt is a crucial aspect of the case and central to the creation of a second majority-Black district anchored in this region.

“The community shares a unique history going back two centuries,” the brief explains. “That history has deep roots in slavery and tenant farming, and includes shared experiences such as navigating economic disruption due to outward migration to urban areas, lack of education and access to basic services, and myriad forms of discrimination, subjugation, and rights denial. Indeed, the seedlings of the nation’s civil rights movement, including the very passage of the Voting Rights Act at issue in this case, were cultivated in Alabama’s Black Belt.” The historians also stress that these commonalities extend to Mobile County, the city of Mobile and other urban areas.

Other highlights:

- A group of social scientists from the University of California, Los Angeles debunk the concept of race neutrality. “Choosing to ignore race in political map drawing is itself an intentional choice with known and predictable discriminatory results,” write the academics. “Race-neutral redistricting by state legislatures and other local jurisdictions does not exist. While technological advances may allow for computer production of race-blind redistricting maps, the people choosing and implementing the final maps are not.”

- Eight Black voters and two nonprofit organizations in Louisiana wrote about how the outcome of the Alabama case will impact the outcome of a pending Louisiana case. “The [Louisiana] Legislature’s disregard of the testimony of Black citizens throughout the [2021] redistricting process is a continuation of a long and unfortunate history of persistent efforts to suppress and dilute the power of Black voters in Louisiana,” write the amici. “This stark history of discrimination, and its contemporary manifestations, illustrate the need for a Section 2 framework.”

- The National Congress of American Indians submitted a brief to explain how Section 2 continues to be an important protection to protect the voting power of Native American communities. In conclusion, the organization put its position simply: “Section 2 must endure.”

Find all of the court documents, including amicus briefs, here. Oral arguments before the Supreme Court are scheduled for Tuesday, Oct. 4 — you can listen to oral arguments here.