How the Census Decides Your Congressperson

The U.S. Census Bureau has released its 2020 census results, giving us all a picture of how the country has changed over the last 10 years — and how populations are dispersed over the 50 states. The census is important for a number of reasons, but today we’re going to talk about one of its biggest uses: redistricting, or the redrawing of district lines to fairly distribute representation in government to voters across the country.

How does redistricting work?

That depends on the state. Once the Census Bureau releases its data, every state is given a new population count — and a new number of seats in the House of Representatives that will now represent them. This number could be the same as 10 years before, or it could be higher or lower, meaning the state needs to add or subtract a district from its maps when it redraws its lines.

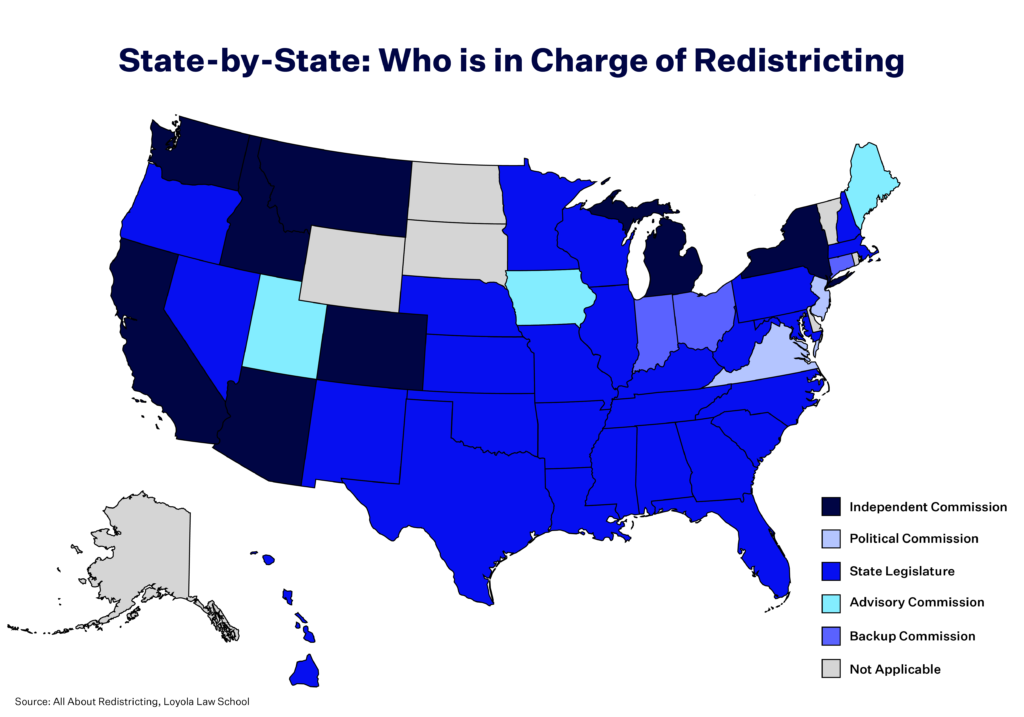

The process of redrawing these lines, however, varies widely from state to state. In the vast majority of states, the legislature controls redistricting and passes new maps for legislative and congressional districts with a simple majority vote. Most of these maps would also need to be approved by the governor, and could be vetoed when they get to his or her desk.

On the one hand, this method creates electoral accountability: politicians are in charge of redistricting and could face accountability for their actions next election. However, this political control also opens up the opportunity for gerrymandering, or the drawing of district lines for political gain. When state legislatures control redistricting, they can essentially choose their own voters, drawing lines they know will benefit their party and suppress the votes of the other.

Gerrymandering is most likely to occur when the same party holds both chambers of the legislature and the governorship. Republicans currently hold 23 trifectas, while Democrats only hold 15. In 17 of the Republican-held states, legislatures control the redistricting process — a significant opportunity for Republicans to gerrymander long-term electoral advantages.

In states where legislatures control redistricting but control of the legislature or governor is split between parties, map drawing can hit an impasse, where the legislature will never be able to pass maps that all parties can agree on. In this case, the state courts often get involved to ensure that an equitable map is enacted in time for the next election. Some states are so reliably unable to reach a consensus in their legislature that we can already assume the courts will get involved: In Minnesota, a court has determined the state’s map every redistricting year since 1970. Only 11 states currently have divided governments, but nine of these give the legislature the power to draw new maps — setting the stage for some significant court involvement as states hit impasses enacting new district lines.

Courts also step in when legislatures pass maps that are unconstitutionally gerrymandered. The map drawn by the Republican Legislature in Pennsylvania after the 2010 census was ruled unconstitutional by the state’s Supreme Court in 2018 due to its discrimination against Democrats: Republicans consistently won 13 of the 18 House seats over the decade after their gerrymander, despite the statewide vote evenly splitting 50/50 between parties in presidential, senatorial and gubernatorial elections.

There are a few nonpartisan solutions to this problem of partisan redistricting, with varying degrees of influence on the process. In some states, “advisory commissions” of non-legislators submit recommendations for maps; however, the legislature still has the final say. Some states have “backup commissions” where statewide officials such as the secretary of state or attorney general take over redistricting if the legislature fails to pass a map by the constitutional deadline. And nine states, including New York and California, have independent commissions that draw their legislative and congressional maps for them, made up of non-electeds who are not public officials. Additional requirements, such as a ban on members of the commission running for office soon after drawing their maps or the barring of legislative staff and lobbyists from serving in this role, help further ensure that the process is nonpartisan and free from the influence of self-interested political actors.

Why does control of the redistricting process matter?

Who controls redistricting is often the easiest way to predict which party will get elected in the following cycle. Republicans are especially prone to drawing maps in their favor, with Republican control of the process resulting in a 9% seat share increase for the party on average. When independent commissions draw maps, states see a significant increase in competitiveness in their elections — meaning that the chances of either party winning a seat are much higher and the advantages for one party are less entrenched.

Competitiveness is important because it means voters feel motivated to turn out, that those in the minority could still win a race and that campaigns are motivated to turn every last vote out to the polls. After California switched to an independent redistricting commission in 2012, the state saw the percentage of House races whose margin of victory was less than 5% spike to 3 times the previous amount. In Arizona, competitiveness in congressional races was higher than the nation as a whole after a commission took over redistricting in 2002. Some studies have even found that independent redistricting can reduce the overall partisanship of the House of Representatives across both parties. Commissions are able to equalize our redistricting process swiftly and effectively.

Republicans made important gains last election in key seats that determined control of the redistricting process. Their strength in state legislatures set them up to artificially gerrymander themselves into power at the federal level, too. Federal legislation like the For the People Act attempts to mitigate this damage by requiring all states to use independent commissions, but the bill has not yet passed into law. We’ll be watching closely to ensure that no unconstitutional gerrymandering denies voters their voice this year — and that Republicans play by the rules.