Moore v. Harper: A Dangerous Theory Has Its Day in Court

On Wednesday, Dec. 7, the U.S. Supreme Court will hear Moore v. Harper. The case, which deals with congressional redistricting in North Carolina, gives the Court the opportunity to review the fringe independent state legislature (ISL) theory.

At its core, the ISL theory is about how the U.S. Constitution should be interpreted when it comes to running federal elections. This theory, thus far dismissed by courts as a fringe and untenable constitutional theory, argues that state legislatures alone have special authority to set federal election rules, free from interference from other parts of the state government such as state courts and governors. This special authority, according to the ISL theory, means that only state legislatures can draw new congressional districts and any map adopted by a state judicial system is unconstitutional. How the Court rules on this issue raised in Moore could shape state legislatures’ power in regulating federal elections — and the checks and balances on this power — for years to come.

Who is involved in the case?

North Carolina Republican legislators asked the U.S. Supreme Court to review North Carolina state courts’ involvement in congressional redistricting and invoked the ISL theory to argue that the North Carolina judicial branch improperly limited the Legislature’s redistricting authority. We’ll refer to this group as the “Moore parties.”

There are two sets of groups that filed the initial lawsuits challenging North Carolina’s congressional map, along with a third party that intervened in the state court litigation, that argue against the ISL theory before the U.S. Supreme Court. These parties include Common Cause, the North Carolina League of Conservation Voters and individual voters. The state of North Carolina and the North Carolina Board of Elections were initially named as defendants in the lawsuits below but are also arguing against any adoption of the ISL theory. For the sake of simplicity, we’ll use “Harper parties” throughout this piece to refer to the side that wants to reject the ISL theory. When we make a distinction between arguments made by the non-state parties (Common Cause et al.) and state parties, we’ll spell out which group made which argument.

How did we get here?

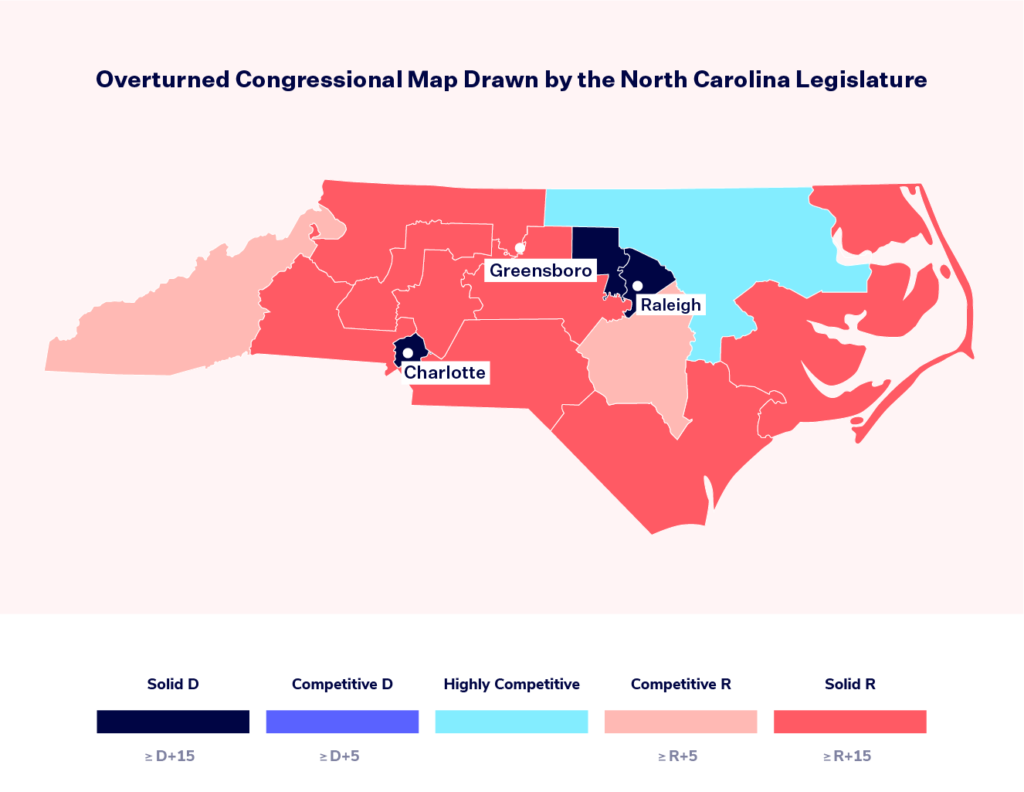

The case now before the U.S. Supreme Court started out as a standard redistricting lawsuit. After a new congressional map was drawn using 2020 census data, litigation over the map’s partisan composition ensued and the map was ultimately struck down by the North Carolina Supreme Court for being a partisan gerrymander that violated the state constitution. (The state’s new legislative maps were also subject to litigation and were similarly struck down for being partisan gerrymanders, but these maps are not relevant to the litigation currently before the U.S. Supreme Court since the ISL theory only implicates federal elections.)

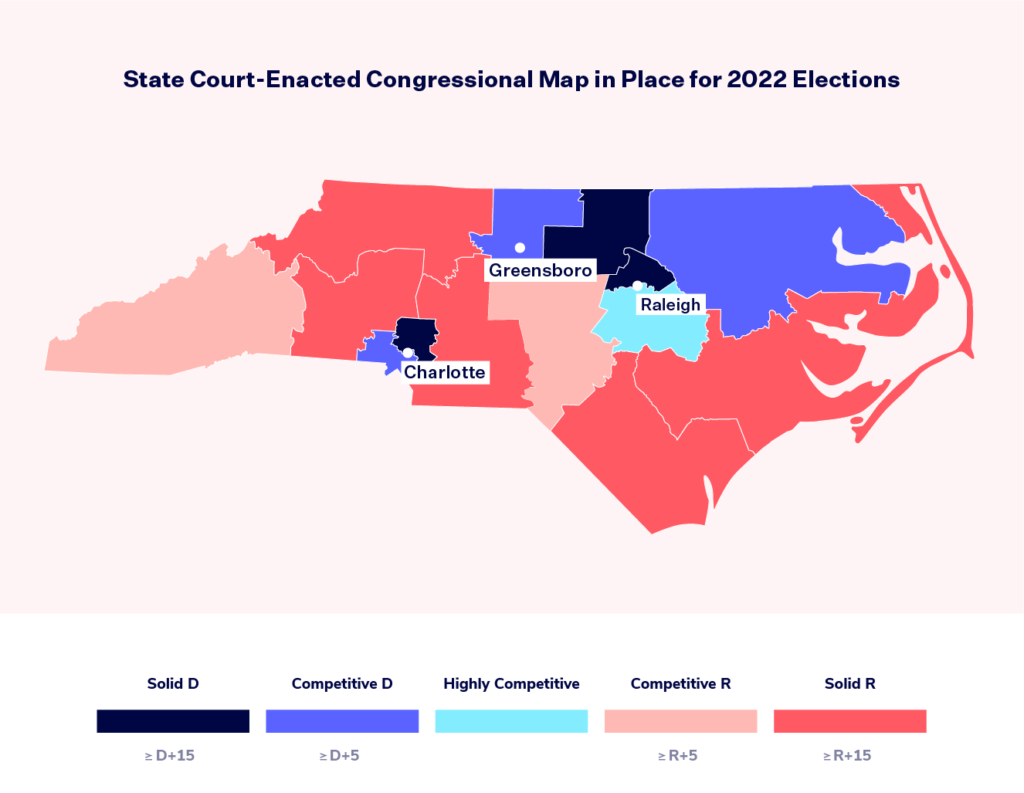

Following the North Carolina Supreme Court’s decision striking down the congressional map drawn by the Legislature, the trial court adopted a new interim congressional map drawn by special masters (court-appointed experts), which was much fairer than the original map, for the 2022 election cycle. However, Republican legislators (the Moore parties) fought the adoption of this map by filing an emergency application on the U.S. Supreme Court’s shadow docket, invoking the ISL theory to argue that the Elections Clause of the U.S. Constitution only allows state legislatures, not state courts, to draw new congressional districts and that the state court system was exercising authority outside its powers in imposing a map for federal elections. The Court denied their emergency application in an unsigned order that offered no supporting explanation, thereby leaving the court-drawn map in place for the 2022 elections. However, over the summer, the Supreme Court granted the Moore parties’ request to review the full case in order to decide whether “a State’s judicial branch may nullify the regulations governing [federal elections]…and replace them with regulations of the state courts’ own devising.” In granting the request to hear the case, at least four justices agreed that the ISL theory — thus far dismissed by courts as a fringe constitutional theory — poses an important, unresolved constitutional issue that requires the attention of the Court.

What is each side arguing before the U.S. Supreme Court?

The question presented (in non-SCOTUS lingo, this means what the Supreme Court is deciding) is: Whether a State’s judicial branch may nullify the regulations governing the “Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives…prescribed…by the Legislature thereof,”” U.S. CONST. art. I, § 4, cl. 1, and replace them with regulations of the state courts’ own devising, based on vague state constitutional provisions purportedly vesting the state judiciary with power to prescribe whatever rules it deems appropriate to ensure a “fair” or “free” election.

Moore parties

In their opening and reply briefs, the Moore parties invoke the ISL theory to argue that the North Carolina Supreme Court improperly imposed state-constitutional limits on the Legislature’s authority over congressional redistricting. They argue that the U.S. Constitution’s Elections Clause “assigns to state legislatures alone the authority to regulate the times, places, and manner of congressional elections” and, accordingly, state courts cannot determine if the rules and maps that a legislature sets for federal elections comply with the state constitution.

The Moore parties contend that the Framers of the U.S. Constitution deliberately chose not to give state courts any role in federal elections, a contention they insist is supported by the historical record and in line with the U.S. Supreme Court’s past precedent. To square their position with the Court’s precedents, the Moore parties concede that “state legislatures are subject to various state-constitutional procedural requirements,” but argue that there is a distinction between procedural and substantive constraints. The Moore parties suggest that because the North Carolina Supreme Court’s decision applied substantive constraints on the Legislature, it is therefore invalid.

Since the Framers didn’t include a role for state courts in federal elections, the Moore parties allege that the North Carolina Supreme Court’s decision to strike down the congressional map and the trial court’s adoption of an interim remedial map represent an unconstitutional usurpation of legislative power that is not authorized by state law. They contend that the U.S. Constitution “place[s] the regulation of federal elections in the hands of state legislatures, Congress, and no one else.” Even though North Carolina state law does specifically authorize judicial review of congressional redistricting plans, the Moore parties argue that the law in question merely allows state courts to review congressional maps for compliance with the U.S. Constitution, not with the state constitution. The state statute allegedly “leaves in place the background rules governing which rules of decision apply.”

The Moore parties also reject the argument that the ISL theory would prevent voters from responding to partisan gerrymandering. They contend that “States would retain a variety of means for dealing with partisan gerrymanders, including the gubernatorial veto, popular referenda [and] independent redistricting commissions” — without acknowledging that North Carolina’s governor doesn’t have a veto over redistricting plans or that referendums or a redistricting commission would require the North Carolina Legislature’s involvement. The remedies the Moore parties cite are either unavailable to North Carolinians or would require the participation of the very body that drew the gerrymander in the first place.

Non-state parties

The non-state parties’ brief — filed by Common Cause, the North Carolina League of Conservation Voters and individual voters — rebuts all of the Moore parties’ arguments. Contrary to the Moore parties’ contention, the non-state parties argue that a state legislature is always “constrained by the [state] constitution that created it” and the Framers drafted the Elections Clause “understanding that state courts would undertake…review to ensure conformance with state constitutions.” According to the non-state parties, the Moore parties’ interpretation of the U.S. Constitution is at odds with the structure of the Constitution and antithetical to the principles of the Framers. To endorse the Moore parties’ argument would allegedly be “a radical departure from the most fundamental principles of the very constitution the Framers had convened to write.”

The non-state parties also reject the Moore parties’ historical arguments, pointing out that a key document on which the Moore parties base their historical claims “is almost certainly a fake.” (In response, the Moore parties state that the “dispute over [the document’s] authenticity” is “inconsequential.”) The non-state parties note that, in reality, a supermajority of early state constitutions regulated congressional elections. Additionally, nearly a century of U.S. Supreme Court precedent rejects the Moore parties’ argument, according to the non-state parties, with the justices unanimously agreeing as recently as 2019 that “state courts could apply substantive provisions in state constitutions to congressional redistricting.” (In response to this, the Moore parties reject this preponderance of historical evidence because it comes from “the second half of the nineteenth century” and is therefore “less probative.”)

The non-state parties also note that even if the Moore parties’ interpretation was correct, the Moore parties would still not prevail because the North Carolina General Assembly specifically authorized judicial review of congressional redistricting plans. Additionally, Congress has exercised its own Elections Clause powers to mandate that congressional plans comply with state constitutions.

The non-state parties end their argument by noting that the Moore parties’ contentions would fundamentally alter federalism by “install[ing] federal courts as overseers, second-guessing state courts’ interpretations of their own state constitutions” and “would upend election administration nationwide.” They conclude that it “is rare to encounter a constitutional theory so antithetical to the Constitution’s text and structure, so inconsistent with the Constitution’s original meaning, so disdainful of this Court’s precedent, and so potentially damaging for American democracy.”

State parties

While the state parties — which include the state of North Carolina and numerous election officials — are on the same side as the non-state parties, they filed a separate brief that raises slightly different arguments, predominantly focusing on state laws that authorize judicial review of congressional maps passed by the General Assembly.

The state parties argue that the Supreme Court doesn’t need to consider the Moore parties’ sweeping Elections Clause claims because the General Assembly “prescribed a detailed statutory scheme authorizing judicial review of congressional redistricting to ensure that it complies with state-constitutional requirements.” Since “[e]verything the state courts did here fell within that explicit grant of statutory authority,” nothing about the process violates the U.S. Constitution and the Moore parties’ attempt to get around these state laws fail on numerous grounds. Finally, the state parties point out that the Moore parties’ claims about the remedial congressional map are irrelevant, as the North Carolina Supreme Court has yet to issue a final decision about the remedial map and, as a result, the U.S. Supreme Court “lacks jurisdiction” (meaning authority to review the case).

The state parties also largely echo the non-state parties’ arguments about the Moore parties’ interpretation of the Elections Clause, stating that “[t]ext, history, and precedent all show that state legislatures must comply with their constitutions when they carry out the responsibilities assigned to them by the Elections Clause.”

Amicus briefs

Earlier this fall, a total of 69 amicus briefs were submitted to the U.S. Supreme Court — 16 in support of the Moore parties that embrace the ISL theory, 48 in support of the Harper parties that repudiate the ISL theory and five in support of neither party. These briefs clue us into what’s at stake and, importantly, who supports this radical theory and who does not.

What’s at stake?

If the ISL theory is validated by the Supreme Court, state lawmakers would have remarkable power to set federal election rules without oversight from state courts or state constitutions. State courts could lose the power to do their jobs — interpreting state law and enforcing their state constitutions — in the sphere of federal elections. State legislatures could set federal voting and election rules and draw congressional maps without historically common and much-needed oversight. At its strongest, the ISL theory could also threaten gubernatorial veto power over federal election rules, citizen-led ballot measures changing election laws and independent redistricting commissions that draw congressional maps.

While this may sound absurd and far-fetched, the mere fact that the Court accepted this case on its merits docket should ring alarm bells. For decades, Republicans have been attacking voting rights from every possible angle, and now their fight made it to the nation’s highest court. With the power of state courts hanging in the balance, the stakes for democracy are immense. Moore v. Harper threatens the ability of individuals, organizations and states to combat suppressive voting laws and expand access to the ballot box through fair maps and inclusive voting practices.

All of this legal discussion surrounding this landmark case — which accompanies yet another crucial voting rights case on the Court’s docket this term — should not distract from the fact that the decision the Supreme Court hands down in Moore will affect voters, specifically minority voters, in very real ways. And, if these litigation tools are obliterated by the Supreme Court, there will be even fewer legal options available to fight back.

What’s next?

After a year of rapid-fire litigation, the fight over North Carolina’s congressional map has culminated in a battle over the application of the U.S. Constitution regarding federal elections. Oral argument before the nation’s highest court will take place on Wednesday, Dec. 7 at 10 a.m. EST. During the hearing, the Moore parties will receive 45 minutes in total for their arguments; the non-state Harper parties will receive 15 minutes; the state Harper parties will receive 15 minutes and the U.S. solicitor general representing the United States will receive 15 minutes (the solicitor general is often granted permission to participate in oral argument when the United States has a vested interest in upholding federal laws, even when it’s not a party to the lawsuit).

You can listen to a live stream of the oral argument here and follow Democracy Docket’s live coverage here.