Nearly Two Years Later, Georgia’s Congressional Map Heads to Trial

In December 2021, Georgia enacted congressional and legislative maps following the release of 2020 census data. Republican state lawmakers controlling the state’s redistricting process worked hard to further enshrine Republican control for the following decade by gerrymandering the maps in their favor. Despite Georgia’s increasingly diverse demographic makeup, the enacted congressional and state legislative maps unfairly dilute the voting power of voters of color.

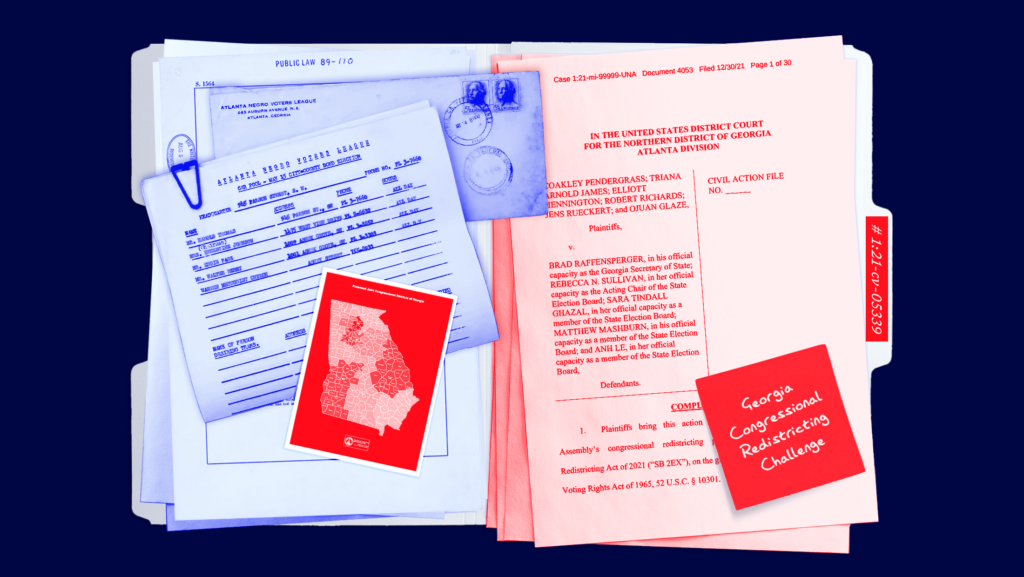

Following the passage of Georgia’s new congressional map, voters quickly sued, arguing that the new congressional map violates Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA). Two other lawsuits, Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity v. Raffensperger and Grant v. Raffensperger are also challenging the state’s legislative maps under Section 2. Litigation has since been ongoing, and was able to proceed thanks to the Supreme Court’s decision upholding Section 2 in Allen v. Milligan. Today, the challenges to Georgia’s legislative and congressional maps are going to trial.

After a historic few years in which Georgia voters sent now-President Joe Biden to the White House and gave Democrats a majority in the U.S. Senate, the outcome of a lawsuit challenging Georgia’s congressional map has the opportunity to once again thrust the Peach State into the national spotlight. Here are the details on the congressional map, and where the critical Section 2 case challenging it stands ahead of today’s trial.

Georgia has a history of discriminating against Black voters and trying to pass discriminatory maps.

As detailed in the complaint, Georgia has an extensive history of discriminating against Black voters. Shortly after the 1868 presidential election in which Black Georgians were able to vote for the first time, “a quarter of the state’s Black legislators were either jailed, threatened, beaten, or killed.” From that moment on, attacks against Black voters in the state would only continue. The Ku Klux Klan threatened violence against Black residents who dared to cast their ballot. The state instituted a poll tax, the first in the country, which reduced turnout amongst Black voters by half.

As recently as 1962, 48 of Georgia’s 159 counties required segregated polling places. Literacy tests, voter challenges and residency requirements not too dissimilar to the ones we still see today plagued Black voters in the state. The state passed electoral maps so egregious that between 1965 and 2013, when the state was under federal preclearance, the U.S. Department of Justice sent over 170 preclearance letters objecting to various maps. And now, more than 150 years after Black Georgians were granted suffrage, they find themselves in a battle fighting to fairly participate in the political process once again.

Pro-voting groups challenged Georgia’s congressional map, arguing for a second majority-Black district.

On Dec. 30, 2021, Black voters in Georgia filed a lawsuit — Pendergrass v. Raffensperger — challenging the enacted congressional map. The voters allege that the Georgia Legislature drew redistricting lines in a way that illegally dilutes Black voting power and deprives Black voters of the opportunity to elect their candidate of choice. Describing realities on the ground, the pro-voting groups argue that “the 2020 census data make clear that minority voters in Georgia are sufficiently numerous and geographically compact to form a majority of eligible voters…in multiple congressional districts throughout the state, including an additional majority-Black district in the western Atlanta metropolitan area.”

Rather than adding another majority-Black district, the complaint alleges that Georgia state lawmakers “cracked” and “packed” Black voters into adjacent majority-white districts. While Black voters in the Atlanta metro area were “packed” into the 13th Congressional District, the rest of the surrounding Black communities were “cracked” between four other congressional districts, which the plaintiffs argue violates Section 2 of the VRA, a key protection that prohibits the “denial or abridgement of the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color.” In a landmark decision earlier this summer, the Supreme Court upheld Section 2, allowing the core claim of Pendergrass to proceed unencumbered by a new interpretation of Section 2.

Roughly two weeks after the lawsuit was filed, plaintiffs in the case asked the court to block the map for the 2022 election.

However, the map remained in place for the 2022 midterms. The Purcell principle was used once again to excuse egregious violations.

On Feb. 28, 2023, two months after the lawsuit was filed a federal judge denied the plaintiffs’ request to temporarily block the map, keeping the map in place for the 2022 election. Despite finding that the plaintiffs were indeed likely to succeed on the merits, the judge wrote that “relief is not in the public’s interest because changes to the redistricting maps at this point in the 2022 election schedule are likely to substantially disrupt the election process.”

The decision was largely based on the Purcell principle, the idea that that courts should not change voting or election rules too close to an election in order to avoid confusion for voters and election officials alike. Originating from a 2006 U.S. Supreme Court case that reinstated a voter-suppression law ahead of Election Day, the principle has been used inconsistently ever since, opening the door for unnecessary voter disenfranchisement and unfair districts in the supposed name of stability.

The judge rejected Republicans’ fringe argument and allowed the case to proceed.

Around the same time that the plaintiffs asked for the map to be temporarily blocked, the defendants in the case filed a motion to dismiss the case, which the judge ultimately denied. Republicans in the case had argued for a dismissal on two grounds: first on a technicality, and second, on the grounds that a private right of action — which allows individuals or organizations, rather than just the U.S. Department of Justice, to bring lawsuits under certain statutes — does not exist under Section 2.

Conservatives have made a habit of attempting to undermine private litigants’ ability to bring Section 2 cases, with the goal of making it harder to challenge Republican-initiated voter suppression and unfair maps. Thankfully, the judge in the case saw through this, writing that the plaintiffs could bring the Section 2 case in Georgia because “for the past forty-five years, the Supreme Court and lower courts have allowed private individuals to assert challenges under Section 2 of the VRA” and that he was not willing to “‘break new ground on this particular issue.”

After the 2022 midterms, plaintiffs and the Georgia officials submitted their arguments to the court, but the judge determined there should be a trial.

After submitting expert testimony to the court, plaintiffs in the case argued that their experts had only reinforced what the judge had previously said was likely true: Georgia’s congressional map violates Section 2 by failing to have a second majority-Black district. The plaintiffs also argued that the defendants had been unable, or unwilling, to refute the evidence presented. Now that the midterm elections had passed and the Purcell principle was seemingly now irrelevant, the plaintiffs argued that a judgment on the merits was warranted.

The defendants, on the other hand, claimed that the plaintiffs had failed to satisfy the preconditions necessary to their Section 2 claim as laid out in Thornburg v. Gingles.

In mid-July, the judge ruled that “there are material disputes of fact and credibility determinations,” and sent the cases to trial.

After two years since the original lawsuit was filed, the case finally heads to trial today.

The case now heads to trial starting today. The trial is expected to take nine days, and Pendergrass (the congressional case) will be tried in conjunction with the two cases challenging the state legislative maps. During the trial, both parties will present evidence, hear from experts and argue for what they deem to be the appropriate recourse.

After the trial ends, it will be up to a judge to decide if Georgia’s congressional map violates Section 2 of the VRA.