Redistricting Rundown: Florida

Prior to the start of redistricting, Florida was not expected to have a particularly contentious process. Republicans hold solid majorities in both houses of the Legislature as well as the governorship. More than that, many analysts described Florida as a potent weapon the GOP could use to help gerrymander its way to a U.S. House majority as Florida gained a new district this year and has the third most House seats of all the states. But redistricting soon became bogged down in a standoff between Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) and the Legislature that may force courts to draw the map instead. Here’s what’s happened so far in Florida and why the redistricting process went off the rails.

Early maps hinted at potential disagreements among Republicans.

Redistricting in Florida got off to a slow start at the end of 2021 when the Florida Senate and the Florida House released their own separate proposals for new congressional maps. The first round of drafts hinted at early disagreements among Republicans, particularly over how to handle the Tampa Bay and Orlando areas, how aggressively to gerrymander and which districts were legally protected to preserve minority voting strength.

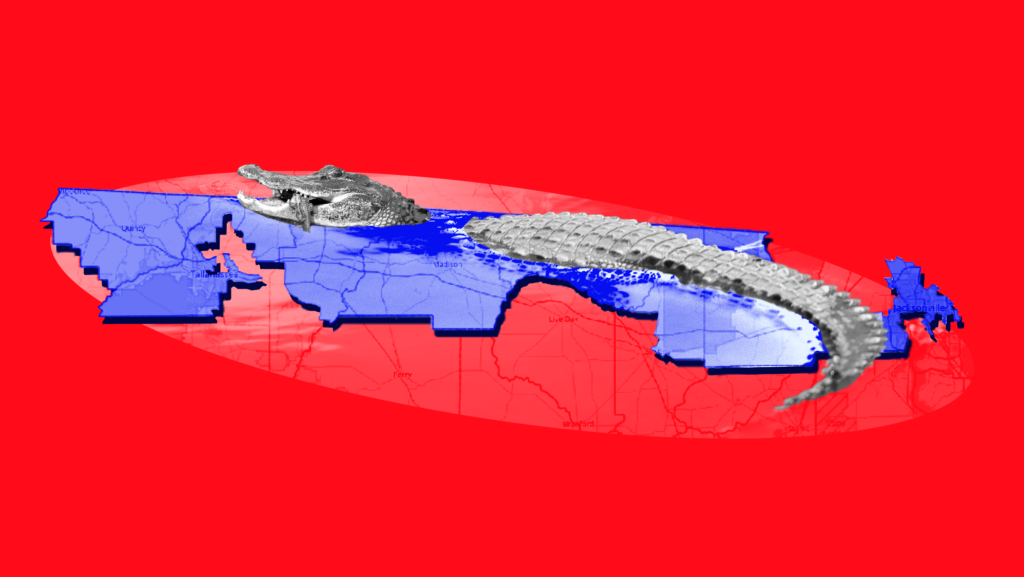

But there was one thing the Florida House and Senate were on the same page about: the configuration and location of the 5th District currently represented by Rep. Al Lawson (D). Created in 2015 following extensive litigation under the state’s Fair Districts Amendment, the 5th District spans northern Florida from Tallahasseee to Jacksonville to unite Black voters in both cities and rural counties in between and give them an opportunity to elect a representative of their choice. Both the Florida Senate and House preserved the district in all of their drafts, agreeing the district was legally protected to ensure Black Floridians maintain their representation.

Redistricting action began to pick up after the start of the new year ahead of the deadline to file for primary elections on April 29. The Senate’s redistricting committee approved a draft congressional map on Jan. 13 with near-unanimous support. Senators from both parties praised the plan, with Democrats describing the proposal as a reasonable attempt to comply with the Fair Districts Amendment and avoid another round of lengthy and costly litigation. While there were still differences to work out with the Florida House, everything seemed on track to pass a congressional plan before the Legislature’s regular session was set to end on March 11. But just a few days later, DeSantis (R) unexpectedly weighed in on redistricting.

DeSantis objected to the Legislature’s plans to preserve the 5th District.

On Jan. 16, DeSantis upended redistricting when he unveiled his own proposed congressional map, becoming the first governor in recent years to wade into a process that is usually dominated by the Legislature. His proposal was far more aggressive than any of the other plans under consideration, increasing the number of Trump-won districts and reducing the number of districts where Black voters can elect their candidate of choice from four to just two. Unlike the House and Senate proposals, DeSantis’ plan completely dismantled the current configuration of the 5h District, which DeSantis argues is an unconstitutional racial gerrymander due to its length and shape.

DeSantis’ proposal was not well received. Political analysts suggested it was more of a political stunt to bolster DeSantis’ conservative credentials and would not pass judicial scrutiny. Meanwhile, the Senate went ahead and passed its preferred plan that preserved the 5th District entirely, suggesting legislators intended to ignore the governor.

DeSantis then asked the Supreme Court of Florida for an advisory opinion over the legality of the 5th District. This move essentially paused congressional redistricting while the governor and Legislature waited for the court’s decision. On Feb. 10, the court declined to issue one, finding that DeSantis’ request “is broad and contains multiple questions” that are better answered through normal judicial review via court challenges. Undeterred, DeSantis submitted a second proposal to the Legislature on Feb. 14 that still dismantled the 5th District. He even paid for a consultant to fly to Tallahassee and testify before the House against the current configuration of the 5th District.

The Legislature eventually passed a congressional plan on March 4 with two maps — a primary map and a backup map if the first is struck down by courts. The primary map, in a concession to DeSantis, shrinks the 5th District to just contain Jacksonville but would potentially still afford Black voters the ability to elect a representative of their choice. The backup map maintains the 5th in its current configuration. Yet DeSantis pledged to veto both maps before the Legislature even finished voting on them, suggesting his real complaint with the district was not its shape but its likelihood of electing a Democrat.

With DeSantis expected to veto, multiple impasse lawsuits have been filed.

With DeSantis threatening to veto the redistricting plan passed by the Legislature, the chance of an impasse requiring the courts to step in is high. Accordingly, two impasse lawsuits were filed on March 11, one in state court and the other in federal court. Both lawsuits argue the “near-certain” impasse and the approaching 2022 elections require a court to implement a new map, especially since Florida has been apportioned an additional seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. If courts take over redistricting, an already muddy redistricting picture in Florida will become even less clear, as it’s hard to predict what kind of map a court will produce.

Florida’s unexpectedly contentious redistricting process illustrates how different redistricting priorities can cause even politicians from the same party to disagree. In Florida’s case, DeSantis’ desire to bolster his conservative credentials by pushing for an aggressive gerrymander clashed directly with the Legislature’s interest in drawing a map that can withstand legal scrutiny. Florida also demonstrates one of the ugly truths about redistricting in American politics: that Republican gerrymanders often come at the expense of minority voters.