Redistricting Rundown: Texas

Late Monday night, the Texas Legislature finished its redistricting special session when it gave final approval to a new congressional map for the state’s congressional districts. State legislative maps were passed last Friday. All three plans now await the signature of Gov. Greg Abbott (R). The new districts will be used for the 2022 elections.

Unlike Ohio and Colorado, the subjects of our first two redistricting rundowns, redistricting in Texas is still under control of the Legislature — and therefore under full control of the Republican Party. This year is also the first time in decades Texas doesn’t have to seek prior approval from the federal government for its maps under the Voting Rights Act (VRA). As a result, the Texas GOP had a free hand to enact a redistricting plan that both protects Republican incumbents and dilutes the voting power of minority voters.

Texas has a history of violating federal law and the U.S. Constitution when redistricting.

Texas is no stranger to controversial redistricting. Since the enactment of the VRA in 1965, a federal court has ruled every single decade that Texas violated federal law or the U.S. Constitution when drawing new congressional and legislative districts. In the 1970s, Texas was added to the list of states subject to preclearance under the VRA due to its history of discriminating against Latino and Black voters. More recently, in 2003, Texas Democrats broke quorum when House Majority Leader Tom DeLay (R) orchestrated a partisan redraw of the state’s congressional districts that ultimately led to the GOP picking up six additional seats in the 2004 House election.

The 2011 redistricting cycle was no different. The Legislature passed new maps for Congress and both state chambers during the summer, which were submitted to a District of Columbia federal court for preclearance as required by the VRA. The court refused to approve the maps, forcing a federal court in San Antonio to draw interim maps based for the 2012 elections. In 2013, the Legislature voted to formally enact the court-drawn plans for the rest of the decade, only making minor changes to the state House plan. All three were then challenged in federal court, although the U.S. Supreme Court ultimately only struck down a single state House district for being discriminatory.

Since the last redistricting cycle, however, the Supreme Court struck down the preclearance provision of the VRA in Shelby County v. Holder (2013). This year, Republicans have free rein to redraw districts without any federal oversight for the first time in decades.

The Texas GOP drew new districts designed to protect Republican incumbents from competitive races.

Although the map the Texas Legislature drew in 2011 never went into effect, the court-drawn maps used for most of the past decade still favored Republicans; an analysis following the 2016 election found Texas’ congressional districts gave the GOP about three more House seats than it otherwise would win based on vote totals alone. However, by 2018 the Republican advantage in the state’s congressional delegation became increasingly precarious as Republicans won by thinner and thinner margins. Democrats flipped two congressional seats in Dallas and Houston, and came close in several others thanks to strong Democratic trends in the state’s suburbs. Democrats made similar gains in the Texas House and Senate. While Democrats came up short once again in 2020, the leftward trend continued and President Biden won the largest share of the vote for a Democrat in the state since 1976.

In response to enormous shifts in the Texas suburbs, the Republican-controlled Legislature has drawn new redistricting plans designed to protect the state’s Republican incumbents from these leftward trends. The new maps achieve this by packing and cracking Democratic voters throughout the state, diluting their voting power and decreasing the number of competitive districts. In 2020, the vote margin in the presidential race was less than 10 points in 14 of the state’s congressional districts, a rough measure of how competitive a district is. Under a preliminary version of the new map, the number of competitive districts falls to just three, with Republican- and Democratic-held seats alike becoming safer for the incumbents.

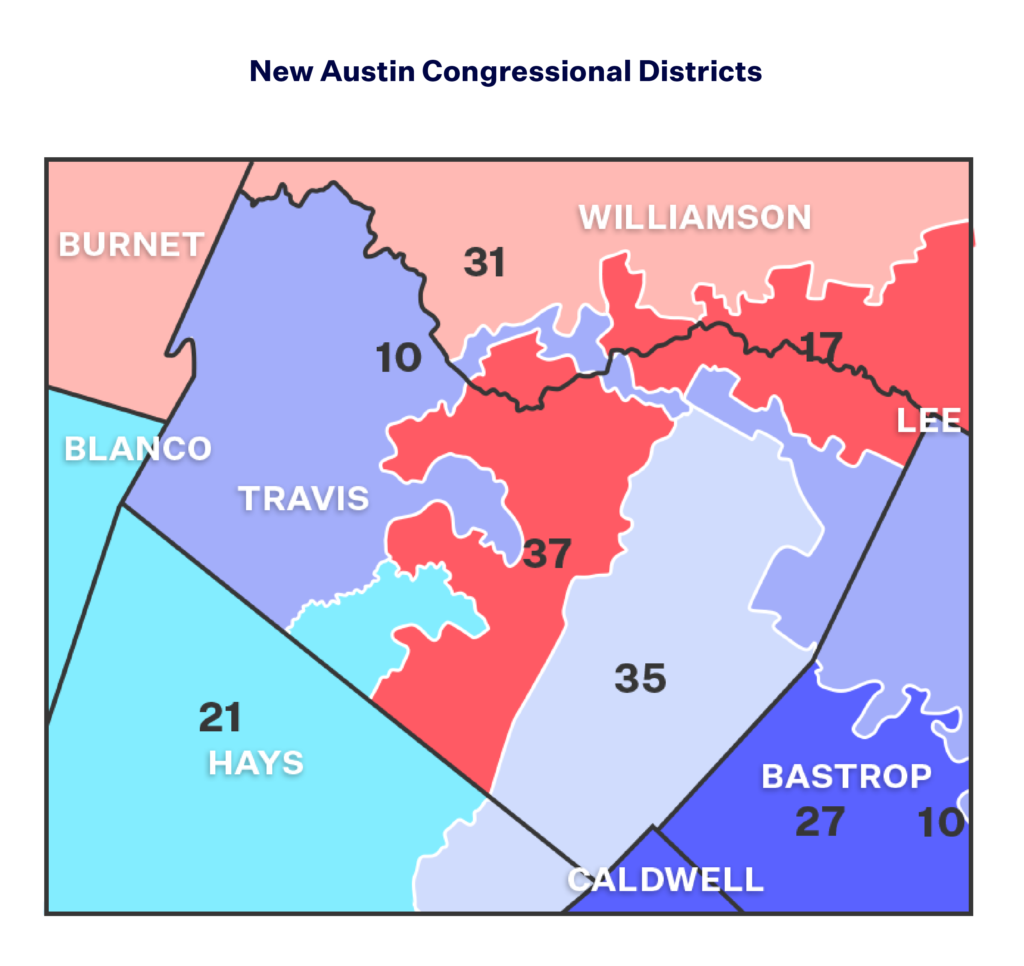

In Austin’s Travis County (the most Democratic county in the state), for example, the Legislature’s plan packs Democrats into the 35th and the newly created 37th Districts. The rest of the county, meanwhile, is drawn into sprawling rural districts dominated by white Republican voters. The 10th District connects western Travis County to a swath of rural counties between Austin and Houston via a narrow land bridge, bolstering incumbent Rep. Michael McCaul (R) by giving him a much more Republican-leaning district than before.

This pattern repeats across the state. Both Rep. Collin Allred’s (D) and Rep. Lizzie Fletcher’s (D) districts (which both flipped in 2018) are made significantly more Democratic to protect surrounding Republican incumbents, whose districts also push further into the countryside to take in more rural Republican voters. Republicans pursued the same strategy in state House and Senate districts, locking in their advantages in the state and precluding the ability of voters to influence the composition of their government through fair, competitive elections.

The new districts also fail to account for the growth of minority communities in Texas.

The new districts also fail to account for the explosive growth of Texas’ minority population. Over the past decade, Texas grew by 4 million residents — 95% of whom are people of color. However, the new districts don’t reflect Texas’s demographic shifts — the maps actually shrink the number of districts where minority voters can sway election results. The census found that only 40% of Texas’ population identifies as white, yet white voters will be a majority in 60% of the new congressional districts, 59% of the new state House districts and 65% of the new state Senate districts.

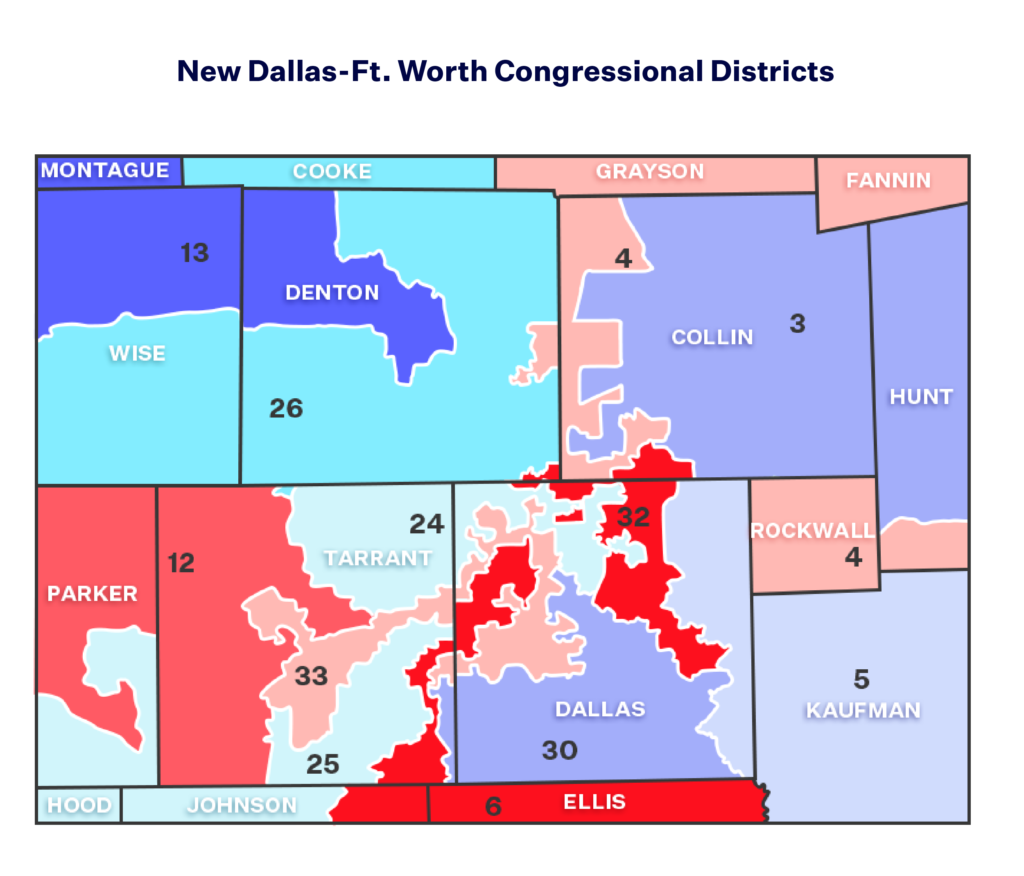

The new Dallas-area congressional districts are good examples of how the Legislature’s redistricting plan dilutes minority voting strength by connecting communities with voters of color to massive districts dominated by white voters. Heavily Latino neighborhoods currently in the 33rd District are grafted onto the rural 6th District, a district where white voters would constitute a majority of the voters. Similarly, portions of the fast-growing Asian community in Collin County are moved from the 3rd District into the 4th, a district that encompasses 11 other counties and stretches nearly 5,000 square miles. The result draws many Asian voters into a district where 73.9% of eligible voters are white and reduces the share of Asian eligible voters in the 3rd District from 10.8% to just 5.6%. Rather than recognize the new multiracial reality of Texas, the Legislature instead sought to lock in white political power in the state for another decade.

Challenges to Texas’ new districts have already been filed, and more are expected.

One challenge has already been filed in federal court against Texas’ congressional, House and Senate districts. The suit, League of United Latin American Citizens v. Abbott, alleges that 1) the state’s current congressional and legislative districts are unconstitutionally malapportioned and that 2) the plans for new districts intentionally dilute the voting strength of Latino communities in violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. The suit asks the court to enjoin the current districts from being used again and order the Legislature to draw new districts that do not dilute the voting power of Latino voters.

Another suit was filed prior to the start of the special redistricting session. Gutierrez v. Abbott, brought by two Texas state senators and the advocacy organization Tejano Democrats, argues the state’s current legislative districts from 2013 are malapportioned. However, it also contends the Texas Constitution prevents the Legislature from redrawing malapportioned maps until the next regular session in January 2023 — essentially, that the state can’t legally draw new legislative districts in a special session. The suit asks the court to draw interim maps to use in the 2022 election cycle. The court has not yet ruled on the merits of this challenge to the state’s legislative redistricting process.

Additional challenges are expected once Gov. Abbott officially signs the new redistricting plans into law.

Texas’ new maps underscore the consequences of Shelby County v. Holder.

Texas’ new congressional and legislative districts inflict harm on the state’s voters: they reduce the number of competitive districts, hampering voters’ ability to influence the government through elections, and dilute the voting power of Texas’ growing minority communities in favor of bolstering white political power. But if the Supreme Court hadn’t gutted the preclearance provision of the VRA, it’s possible these maps would never have been allowed to go into effect. But thanks to the Supreme Court’s ruling in Shelby County v. Holder, it may take years of litigation for these maps to be overturned — if ever. The harm that will be inflicted on Texans in the interim is incalculable.