The U.S. Supreme Court’s Latest Order Could Throw a Wrench in a Major Election Case

Back in December 2022, the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral argument in Moore v. Harper, the landmark redistricting case out of North Carolina that raises the fringe independent state legislature (ISL) theory. With argument complete, normally all that’s left would be for the Court to issue its decision, but two related developments have thrown a wrench in the Court’s usual process.

In February 2023, the North Carolina Supreme Court, with its newly elected Republican majority, agreed to rehear its decision to overturn partisan gerrymanders that led to Moore reaching the U.S. Supreme Court in the first place. Then just last week on March 2, the Court asked for the parties to submit supplemental briefs on whether the Court even has jurisdiction to review Moore in light of the North Carolina Supreme Court’s decision to rehear the case. Both of these developments make it increasingly likely that the U.S. Supreme Court won’t issue a decision in Moore at all.

But the Court could still issue a decision on the merits of the case given that Moore gives the Court the opportunity to review the ISL theory. This theory argues that the U.S. Constitution’s Elections Clause gives state legislatures special authority to set federal election rules, including drawing congressional districts, free from interference from other parts of the state government such as state courts and governors. The case centers on whether the North Carolina Supreme Court violated the Elections Clause by overturning a congressional map drawn by the state Legislature; if the Court accepts the ISL theory, the state court’s actions would be deemed unconstitutional. A ruling endorsing the ISL theory could have dramatic ramifications for American elections, but it all depends on how far the Court is willing to go.

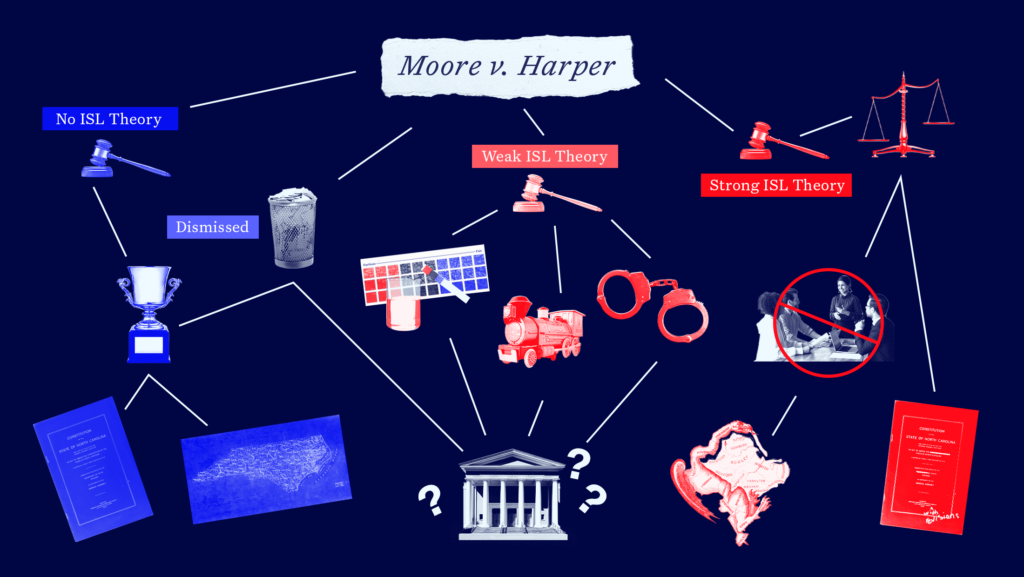

Needless to say, there’s a plethora of ways Moore could end. Here, we outline the possibilities we can expect — both if the Court declines to issue a decision and if it does reach a ruling. Keep in mind that we don’t have access to the internal deliberations of the justices (or a crystal ball) and these possibilities are educated guesses based on what we know at this time.

Procedural developments mean the U.S. Supreme Court may not issue a decision.

The Court’s recent order suggests that the justices are considering dismissing Moore for procedural reasons. It asks the parties in the case to address whether the Court still has jurisdiction to decide Moore under 28 U.S.C. §1257(a), which states that the U.S. Supreme Court only has the power to review final decisions issued by a state Supreme Court. But with the North Carolina Supreme Court reopening its case, it’s possible that there is no longer a final decision for the U.S. Supreme Court to consider, resulting in the Court dismissing Moore as a consequence of this jurisdictional issue. Dismissing the case in this way doesn’t create any precedent about the ISL theory and would allow the North Carolina Supreme Court’s ruling to stand.

But the Court could also dismiss the case as “improvidently granted.” Essentially, this means that the Court would revoke its prior grant of certiorari that put the case on its merits docket and the lower rulings would stand. Similar to the case being dismissed due to a jurisdiction issue, this wouldn’t create any precedent regarding the ISL theory issue in the case. The Court can dismiss any case as improvidently granted for a variety of reasons, such as determining that a case is no longer the right vehicle to decide a legal issue. The developments at the North Carolina level, for example, could lead the justices to conclude that the case is simply too messy or complicated and the Court could dismiss Moore as improvidently granted. The Court doesn’t have to explain its reasoning in this scenario, so if the justices decide to take this route we may never know the explanation behind it.

Both of these outcomes would leave the current status quo regarding the ISL theory in place. The Court would not endorse the theory, so state courts and state constitutions would continue to constrain how legislatures run federal elections. But the Court wouldn’t reject the theory either, meaning the theory will likely continue to appear in litigation and the Court could accept a future case raising ISL theory claims. For example, a redistricting case out of Ohio that poses such claims is currently pending before the Court.

Another possibility to keep an eye out for is if the Court decides to hold Moore over to its next term, which happened in another landmark case, Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010). However, this would merely delay resolution of the case; any of the outcomes delineated in this piece would still be possible.

But if the U.S. Supreme Court does issue a ruling, here are the possibilities we expect.

The Court could still decide to issue a decision no matter what happens with the state-level rehearing. Indeed, some legal scholars expect the Court to issue a decision precisely so that it can rule on the ISL theory issue. We expect a decision on the merits to fall into one of four categories, listed in no particular order.

The U.S. Supreme Court may affirm the North Carolina Supreme Court’s original decision blocking maps for being partisan gerrymanders, but on a narrow ground that doesn’t reach the underlying ISL theory issue. As the pro-voting parties and U.S. solicitor general pointed out in their briefs to the U.S. Supreme Court, the North Carolina Legislature had previously enacted a law that authorizes the state Supreme Court to do exactly what it did in the present case: rule on legal claims against maps to ensure no laws are violated. Accordingly, the U.S. Supreme Court could simply recognize this grant of authority and uphold the lower decision without addressing the ISL theory claims.

Like the procedural possibilities previously outlined, this would leave the current status quo in place, but the ISL theory claims would likely continue appearing in litigation and the Court could end up ruling on it in a different, future case.

The best outcome for voters and democracy would be for the U.S. Supreme Court to unequivocally reject the ISL theory. Not only would this preserve the status quo, but it would also likely close the door on future ISL theory lawsuits. State courts and state constitutions would continue to constrain state legislatures when they set the rules for federal elections, and voters would be able to use the protections enshrined in state constitutions to protect voting rights and fight gerrymandering.

The U.S. Supreme Court could also find a middle ground, neither rejecting ISL theory but not fully embracing it either. Based on oral argument, this seems to be the most likely outcome if the Court issues a decision on the merits of the ISL theory. The justices seemed to reject the most radical claims brought by proponents of the ISL theory, but at the same time agreed that there could be some instances where a state court oversteps its authority when it comes to federal elections and violates the U.S. Constitution.

In this case, the Supreme Court would likely articulate some sort of legal test or rule to determine when a state court or other entity runs afoul of the Elections Clause. This kind of ruling would likely set off a wave of litigation to determine in which circumstances this rule applies. It would take a long time to sort through all the ramifications of the Court’s decision, so this outcome would invite the most uncertainty given that the results of such a ruling would hinge on how lower courts interpret the opinion.

The final possibility would be a full-throated endorsement of the ISL theory, meaning that state courts wouldn’t be able to overturn election rules enacted by state legislatures. The logic of this ruling could then be extended to endanger state governors’ veto power over federal election rules and even the ability of independent redistricting commissions to draw maps. This would be by far the worst outcome for voters, as state legislatures would gain extensive power over the running of federal elections and voters would have virtually no recourse. Thankfully, based on oral argument, such a decision seems extremely unlikely.

Whatever happens, we know the U.S. Supreme Court won’t act before the end of March.

While only the nine Supreme Court justices know for sure what will happen with Moore, we now have a little bit more information about the timing of a potential decision. The Supreme Court’s order set a March 20 deadline for the parties to file supplemental briefing answering its jurisdiction question. As a result, we can be sure that the Court won’t release a decision in the coming weeks. Once briefing is complete, a decision could come at any time and with little advance notice. Whatever happens, we’ll be sure to keep you updated on how the Court rules in Moore v. Harper and what it means for voting and American democracy.