Voter Testimony: The Voices Behind Alabama’s U.S. Supreme Court Case

On Oct. 4, the second day of its 2022 term, the U.S. Supreme Court will hear Merrill v. Milligan, a case that could fundamentally alter the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA). The most litigated section of the VRA, Section 2, protects against any voting law or district map that results in the “denial or abridgement of the right of any citizen of the United States to vote on account of race or color.” In practice, this provision has been an important tool to fight against laws that were enacted with a discriminatory purpose or have a discriminatory impact.

On Tuesday, Oct. 4 at 10 a.m. EDT, the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in Merrill v. Milligan, a case that will decide the future of Section 2.

Now, a case out of Alabama is putting Section 2 to the test. Following the release of 2020 census data, the Alabama Legislature redrew the state’s seven congressional districts, maintaining a single majority-Black district. After the new map was adopted in November 2021, three sets of plaintiffs sued — all alleging racial discrimination but with different arguments. The parties in Milligan, which was consolidated with another lawsuit Caster v. Merrill, argued that the map violates Section 2 of the VRA by diluting the voting power of Black voters. (There were also 14th Amendment racial gerrymandering claims at play, but these were not ruled on and remain a distinct concept from a Section 2 racial vote dilution claim.)

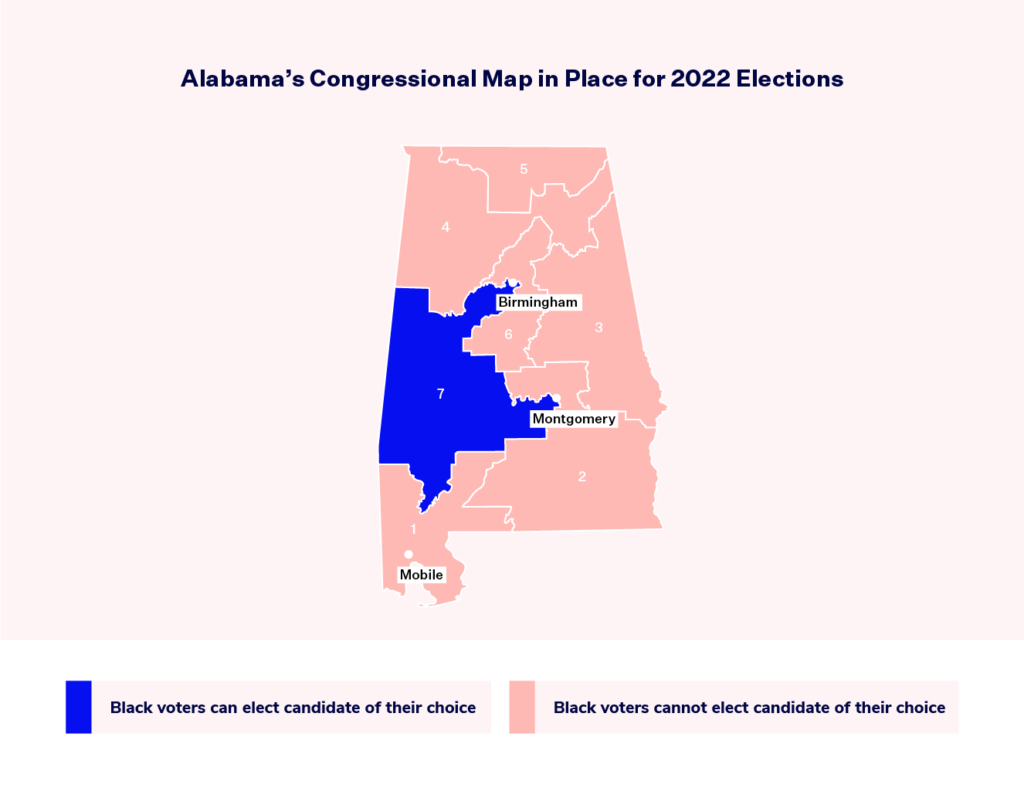

In January 2022, a lower court determined that the map likely violated Section 2 of the VRA and ordered the Legislature to redraw a VRA-compliant map, specifically one that has a second majority-Black district. Instead of following the court order, the state of Alabama accelerated the case to the U.S. Supreme Court, which paused the lower court’s order via its shadow docket. This means that Alabama’s previously blocked map with only one majority-Black district is in place for the 2022 elections.

In our third Voter Testimony piece, we’re familiarizing ourselves with the case in advance of its visit to the nation’s highest court. Amidst the technical, even mathematical, nature of redistricting cases, it’s important not to lose sight of the human impact of inadequate representation. Here’s what we gleaned from the post-trial briefs and transcripts from the seven-day hearing held in January.

Experts demonstrated how Alabama’s environment fulfills key legal requirements.

On Oct. 4, we can expect the Supreme Court justices to discuss the Gingles factors. This legal criteria comes from a 1986 Supreme Court case, Thornburg v. Gingles, where the Court established three factors that need to be satisfied to show a pattern of racial vote dilution under Section 2: (1) The minority group in question must be “sufficiently large and geographically compact” to constitute a political district; (2) the minority group must be “politically cohesive,” meaning the group generally votes for similar candidates and (3) the majority group must also be “politically cohesive” and vote to defeat the preferred candidates of the minority group. The second and third factors together demonstrate racially polarized voting.

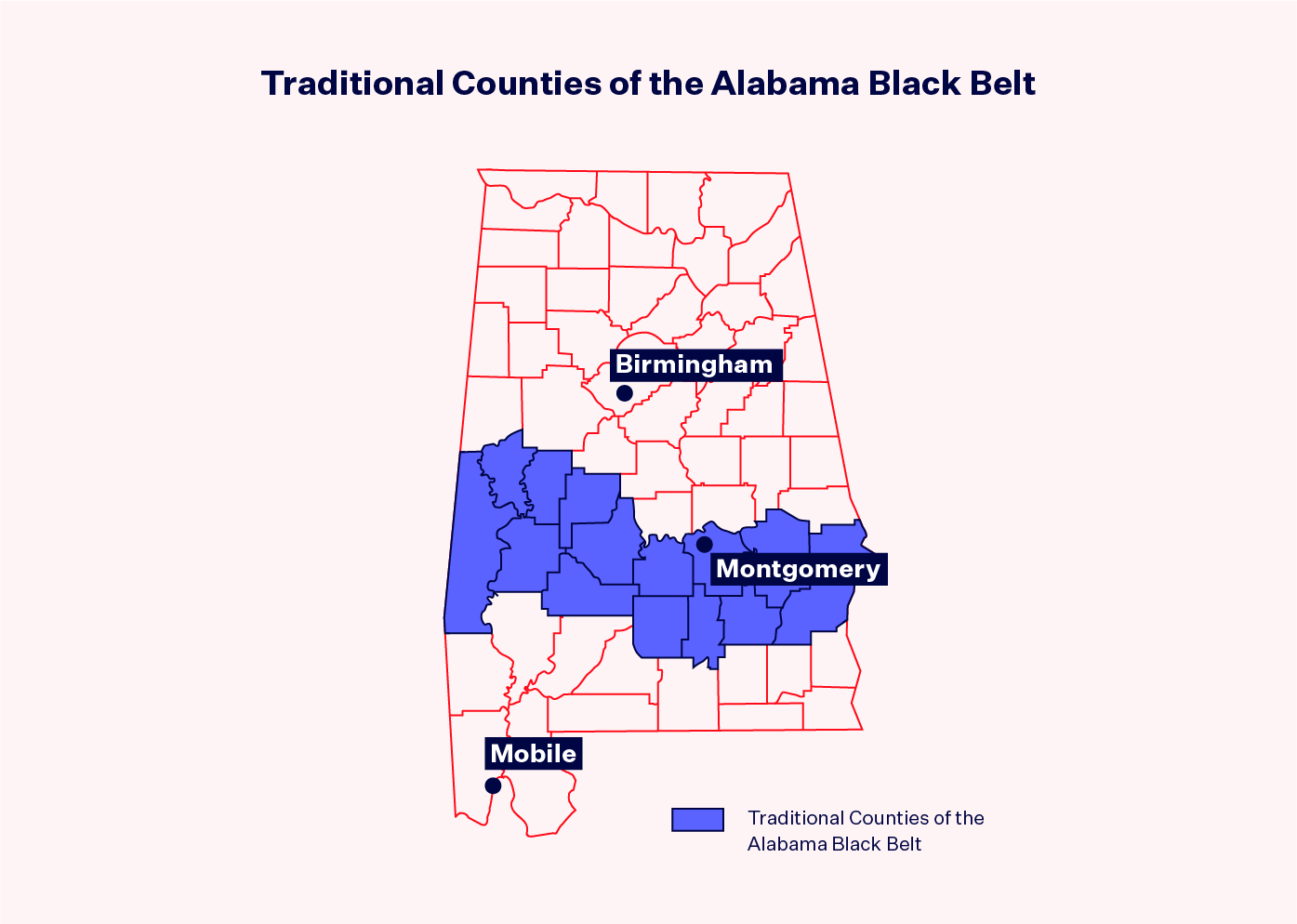

First, is Alabama’s Black population “sufficiently large and geographically compact” enough? The plaintiffs’ experts, often academics, responded with a resounding yes. According to the 2020 census, Black residents in Alabama compose over 27% of the population. The Black population share in the major cities of Birmingham, Mobile and Montgomery is over 50%, and there are 49 other majority-Black cities in the state. Additionally, about a quarter of Alabama’s Black population lives in a stretch of rural counties known as the Black Belt that has significant ties to several of the urban areas.

Next, experts conducted racially polarized voting analysis to show how the state satisfies Gingles factors two and three. For example, the 2020 congressional elections show how both the minority group and majority group are “politically cohesive,” but the latter defeats the former’s preferred candidates, especially when those candidates are Black themselves.

- In the 2020 general election in the 1st Congressional District, the Black candidate received 93.3% of votes cast by Black voters and 12.6% from white voters.

- In the 2020 general election in the 2nd Congressional District, the Black candidate received 93.4% of the votes cast by Black voters and 5.2% from white voters.

- In the 2020 general election in the 3rd Congressional District, the Black candidate received 92.6% of the votes cast by Black voters and 6.6% from white voters.

Another notable statistic: In the 2008 presidential election, Republican Sen. John McCain received 51% of votes from white Democrats, and 88% of all white voters in Alabama. (In contrast, President Barack Obama garnered an astonishing 98% of votes cast by Black Alabamian voters.)

With a shared history, the Black Belt represents a community of interest.

The Black Belt is a region in Alabama that runs through the center of the state and is named for its dark, fertile soil. Consequently, the cotton production in this area “made a lot of white landowners very, very rich, and the labor was being done of course primarily by enslaved black persons,” explained historian Dr. Joseph Bagley. Even after the end of slavery, sharecropping became prominent and, according to Bagley, its legacy persists: “The Black Belt remains characterized by its mostly black population [and] by the fact that it is stricken by poverty.”

The Black Belt covers a vast area in the state, stretching from the borders of Mississippi to Georgia, and is currently divided among several different Alabama congressional districts. However, throughout the hearing, experts and witnesses with personal knowledge discussed the strong ties between Black Belt counties, specifically the connections between the city of Montgomery and communities in the eastern Black Belt and the city of Mobile and the western Black Belt.

When pushed by the defendants’ lawyers about the long distance between the disparate parts of the Black Belt, lead plaintiff Evan Milligan responded: “Can a black person in Mobile share something in common with a white person in Mobile? For sure…But I think the other question is: Can [a Black person in Mobile] share something very deep and relevant and common with their neighbors throughout the Black Belt with their relatives in similar living conditions as those Black Belt counties, which may extend as far as the Georgia line. And I think that is also true.”

Another Black resident testified about her family’s migration from the Black Belt, where some family members still live, to Mobile, a city on Alabama’s Gulf Coast. “We have the port. We have factories down here,” the witness explained, referencing Mobile’s economic opportunities. “There are some people from the northern counties that drive down to work at the ports on the coast of Alabama.”

Black Alabamians testified about feeling overlooked and unrepresented by their white, Republican members of Congress.

A recurring theme among witnesses was a sense of inadequate representation in Congress. In the current map configuration, Black voters compose a significant portion (25 to 30%) of the population in the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Congressional Districts. Yet, because these communities are split over these three districts, they cannot elect the candidate of their choice in any of them. Milligan, who is also the executive director of Alabama Forward, spoke about that disempowerment.

I think there is a direct correlation between the lack of agency that black voters feel, you know, in Montgomery and in places where you see the splitting of the districts…[A second majority-Black] district would provide more buy-in for those communities and more of an incentive to make, you know, longer term commitments, and even see themselves as leaders of those communities.

Marcus Caster, a Black voter currently in the 1st Congressional District, reiterated that sentiment.

I continue to vote, but I do not feel as though…my voice is being heard because we’re not getting someone that’s representing the black community.

Benjamin Jones, a Black resident in the district represented by Rep. Barry Moore (R-Ala.), described the fact that the conservative candidate will win the general election as almost a “foregone conclusion.” For Jones and others, it feels as though their members of Congress don’t care about remedying the issues plaguing Black communities. Shalela Dowdy pointed to Rep. Jerry Carl’s (R-Ala.) opposition to specific legislation, such as the Build Back Better Act and emergency funding for baby formula, that would have made a difference.

I am not confident that [my congressman] is adequately representing me based off of bills that he has chosen not to support…We have issues in our community that can be rectified by supporting these bills. And we don’t have the right person in these elected positions who will vote for the things that can help fix the issues we have in our community.

In contrast, Rep. Terri Sewell (D-Ala.), who represents the majority-Black 7th Congressional District, supports legislation that witnesses identified addresses systemic issues facing Black communities in Alabama. Collectively, the witnesses brought up the persistent disparities in employment, healthcare, incarceration and education between Black and white and residents, as well as long-standing problems with infrastructure, cost of child care, internet access and more. Caster emphasized the importance of having elected officials who care deeply about solving these concerns.

I think it would be more beneficial to the black community to have someone…that will be able to listen to the citizens in our community, that would visit the citizens in our community, that would go to Washington to represent us and to vote on bills that represent our community would be very beneficial to the district, our district.

The upcoming oral argument at the Supreme Court will only be one hour long and the justices will only hear from the lawyers in the case. On that day, let’s not forget about the voices behind the litigation and the decades-long struggle for fair representation in Alabama.