What’s Next in Republicans’ Legal War on Voting Rights

In June, Republican efforts to restrict voting rights suffered two setbacks at the U.S. Supreme Court. At the beginning of the month, the Court upheld a lower court decision requiring Alabama to draw a second majority-Black district in the case Allen v. Milligan. The decision, authored by Chief Justice John Roberts, left the current application of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA) intact; he declined to acquiesce to Alabama Republicans’ desire to weaken the landmark law.

Then, at the end of the month, Roberts refused to endorse the fringe independent state legislature (ISL) theory in the case Moore v. Harper. Republicans in several states, principally North Carolina but also in Ohio, had used the theory to argue against state court action, contending that state legislatures have special authority to set the rules for federal elections. Roberts disagreed, writing that the U.S. Constitution “does not exempt state legislatures from the ordinary constraints imposed by state law.” The decision represents another important win for voting, as it preserves the ability of state courts across the country to protect voters from restrictive election laws and gerrymandered congressional maps.

But these two victories don’t mean that voting rights are completely safe. Republicans aren’t just going to give up; they’ll lick their wounds, regroup and settle on a new target. Already, we can see the first rumblings of the next Republican legal strategies echoing in lawsuits, court filings and legal opinions across the country.

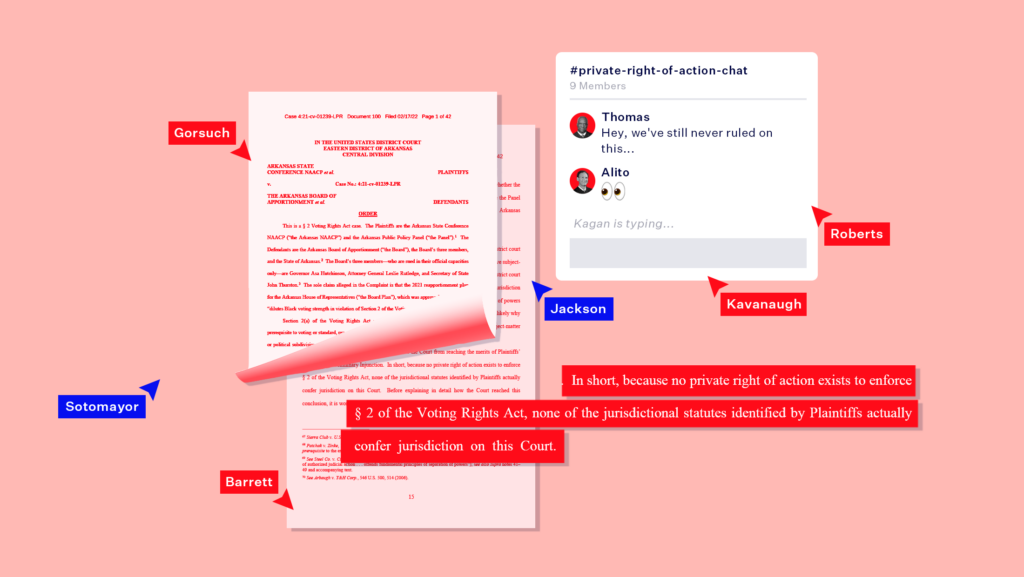

The private right of action could be next.

One potential target brewing in conservative legal circles is the private right of action, a legal mechanism that allows private litigants to bring lawsuits challenging violations of federal civil rights laws. Without a private right of action, only the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) would be able to bring lawsuits, leaving the enforcement of civil rights laws like the VRA up to the whims of the current U.S. attorney general. And even when a presidential administration is supportive of voting rights, the vast majority of Section 2 lawsuits, for example, are brought by private plaintiffs — during President Joe Biden’s term, the DOJ has only filed two Section 2 cases while private plaintiffs have brought 30.

Already, the private right of action has come under attack, as undermining it would allow Republicans to severely hinder the operation of civil rights laws without having to get rid of the laws completely. It seemingly started in Arkansas in 2022, when a federal judge, appointed by former President Donald Trump, ruled that there is no private right of action under Section 2. That decision has been appealed to the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals and we await a ruling.

Some members of the U.S. Supreme Court have expressed support for this theory; when the Court decided Brnovich v. DNC in 2021, Justice Neil Gorsuch wrote — and Justice Clarence Thomas joined — a concurrence to highlight the fact that the case “assumed—without deciding” that the VRA has an implied private right of action. As such, the two justices suggest that the private right of action in Section 2 is an open question. Likewise, a footnote in Thomas’ dissent in Allen notes that the Court “does not address whether §2 contains a private right of action,” leaving that door open in future cases.

Meanwhile, other conservative judges have cast doubt about whether the private right of action exists in the Civil Rights Act’s Materiality Provision, a part of the law that protects voters from disenfranchisement on the basis of “an error or omission…if such error or omission is not material in determining whether such individual is qualified.” In other words, it ensures that voters aren’t disqualified because of trivial mistakes. In the wake of Allen, Republicans could seize on this idea as a new front in their war on voting rights.

Louisiana Republicans want to avoid Allen by citing another recent Supreme Court case.

Elsewhere, Republicans are already starting to try to poke holes in Allen to avoid drawing additional minority districts. After the Court handed down Allen, it also unpaused proceedings in a similar case out of Louisiana and sent it back to the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for further litigation. Following that, the 5th Circuit invited the parties to submit additional briefing in light of the decision in Allen.

Louisiana Republicans responded by citing another recent Supreme Court case, Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard College, that ruled that affirmative action programs in college admissions are unconstitutional. Since the Court in the affirmative action case held that “statutes requiring race-based classification…necessarily become obsolete,” Louisiana Republicans suggest this means that Section 2 — which they contend similarly requires classifying voters based on their race — may also no longer apply to Louisiana.

While this seems to fly in the face of what the Court ruled only weeks earlier in Allen, Louisiana Republicans also point to Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s concurrence in Allen for support. In it, he notes the argument that “the authority to conduct race-based redistricting cannot extend indefinitely into the future.” However, because Alabama “did not raise that temporal argument” he does not consider it “at this time.” Thus, Kavanaugh suggested he might be open to such an argument in the future — and his defection to the minority would be all it would take to change the outcome of the case.

Rather than comply with the Court’s ruling in Allen, Louisiana is inviting conservative judges to embrace a new rationale for overturning Section 2. Only time will tell if they go along with this gambit.

The decision in Moore suggests an additional pathway for litigation.

Meanwhile, the Court’s decision in Moore also points to a pathway for future election litigation. While the Court emphatically rejected the ISL theory, the opinion notes that “state courts do not have free rein” and warns that state courts could “read state law in such a manner as to circumvent federal constitutional provisions.” In such cases, federal courts may be required to step in and overturn state court action.

Notably, this was not an argument raised by the litigants in Moore, who repeatedly assured the Court during oral argument that the court decision at issue “fairly reflect[ed] North Carolina law.” As Gorsuch summarized, “nobody here thinks the North Carolina Supreme Court is exercising a legislative function.” Now that the ISL theory has been foreclosed by the Moore decision, it’s likely that litigants will seize upon this angle in future cases. Rather than argue that courts aren’t able to check state legislative actions, they could argue a state court grossly departed from state law.

To be sure, this wasn’t a pathway invented by the Court’s decision in Moore; litigants were free to raise such claims before. But now with the Court’s endorsement, it will likely become a more common tactic, even if it’s unclear how successful such a strategy will ultimately be.

Moore and Allen both represent important pro-democracy victories from this year. But the fight for voting rights won’t end with those decisions. It will merely metamorphosize into new targets and tactics. With increasing skepticism toward the private right of action and novel arguments being advanced by litigants, we may already be seeing the contours of the next battle.