When Election Officials Refuse To Certify Complete Election Results

It’s been over two months since Pennsylvania held its primary elections, but three counties are still refusing to include certain ballots in their certification totals. On July 11, the Pennsylvania Department of State and secretary of the commonwealth sued the three county boards of elections over their obstruction.

This isn’t an isolated, small-scale issue: The counties — Berks, Fayette and Lancaster — have a combined population of over one million people. The skirmish also isn’t simply about Pennsylvania and a specific type of mail-in ballots; the implications of this kind of nuanced election subversion will be widespread in the years to come.

A federal and state court both agreed that the ballots must be counted.

The three county boards of elections are refusing to include in their totals mail-in ballots that were received before Pennsylvania’s 8:00 p.m. deadline on Election Day, but were missing a date on the outside envelope. This might sound like an oddly specific category of ballots, known as “undated mail-in ballots,” but we’ve seen plenty of litigation in the Keystone State itself around this very issue.

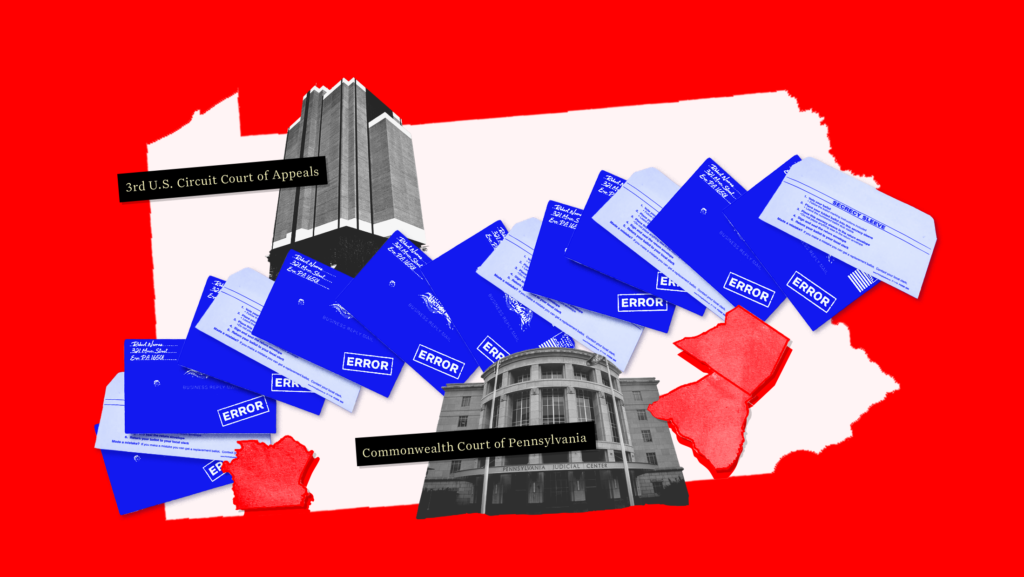

The question first arose in a local judicial election in Lehigh County, Pennsylvania. Several voters in this judicial election who had their votes discarded because of a missing date sued under the Civil Rights Act’s Materiality Provision. The statute protects votes from being discarded for mistakes that are “not material” or unrelated to a voter’s eligibility. In that case, Migliori v. Lehigh County Board of Elections, the 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals agreed that voters should not be disenfranchised for failing to write a date, ruling that the ballots in questions should be counted. The Republican candidate in this judicial race then tried to get the U.S. Supreme Court to stop the 3rd Circuit’s decision, but the Court declined to do so, effectively ending this lawsuit and keeping the 3rd Circuit’s ruling as the controlling precedent.

Around a similar time, trailing U.S. Senate candidate David McCormick (R) filed a lawsuit to ensure that these undated mail-in ballots were counted in his close Senate primary race against Dr. Mehmet Oz. A state court granted McCormick’s request, ordering the ballots to be counted, though McCormick conceded soon after.

Within the span of a week, a federal circuit court and a state appellate court both concluded that not counting undated mail-in ballots would violate the Civil Rights Act. The precedent for local officials to follow, if there was any prior doubt, was now clear.

The three GOP-led counties are flouting the rule of law.

Three counties are holding up the final certification of a primary election from 11 weeks ago. And it’s not a simple misunderstanding — the county commissioners are adamantly fighting back and actively refusing to follow the court orders. Two of the counties wrote in a brief that “the Third Circuit panel’s decision in Migliori was wrongly decided,” pointing to the fact that three dissenting U.S. Supreme Court justices called that decision “very likely incorrect.” (The opinion ignores the fact that at least a plurality of the Supreme Court justices refused to halt the 3rd Circuit’s decision, choosing to cite the dissent instead.)

To reiterate, all of the ballots the three counties are refusing to count were received on time. Pennsylvania election officials stamp the outer envelopes with a date as soon as the ballots are received in order to help them keep track of which ballots were timely. The handwritten date on the outer envelope is not used for this purpose. Additionally, voters often write the wrong date on the outside envelope, jotting down their birthday for example. Despite not including ballots whose envelopes are missing a date altogether, the three uncooperative counties all confirmed that they did, in fact, include “wrongly dated” mail-in ballots in their count. So, are mail-in ballots missing a date any different than mail-in ballots with incorrect dates? Both categories are irrelevant to a voter’s eligibility and the timeliness of their ballot.

On July 28, a hearing took place in the Commonwealth Court of Pennsylvania for the secretary of the commonwealth’s lawsuit against the three counties. On the witness stand, Fayette County Commissioner Scott Dunn (R) explained that he believes there was ambiguity around the court orders and state law about undated mail-in ballots — despite two very clear court rulings — so he decided to not follow the court order as a result. Chair of the Berks County Board of Commissioners, Christian Leinbach (R), displayed a similar attitude, adding that he “could not in good conscience vote to certify undated ballots.”

The attorney for Lancaster and Berks counties argued that the Migliori decision (the federal case that came out of the Lehigh County judicial election) does not apply to all Pennsylvania elections. The presiding judge then followed up: “How could you argue that it would not apply?”

The attorney responded: “Well, I would argue that it is wrong.”

The theme of the July 28 hearing was a complete disregard for the rule of law from the county officials, who admitted they were defying court orders on the personal belief that federal and state courts were “wrong.”

What’s happening in Pennsylvania is a warning sign for future election subversion.

There are two main takeaways from this simmering constitutional crisis. First, issues like this will become more common. Election administration in the United States is highly decentralized, so a refusal to accurately count, canvass or certify election results can take place at any precinct polling place, town, city or county board, state canvassing board or the myriad of other stops in the post-election process. We rely on the local and state officials who handle election certification to act in good faith.

Second, the Pennsylvania counties presented a blueprint for what election subversion could look like — it most likely will not be an absolute refusal to submit or certify results, but rather, and more insidious, a submission of incomplete results that exclude lawful votes. This is harder to detect and requires enforcement from other actors, either the executive branch or private parties. Fortunately, Pennsylvania currently has a pro-voting governor, secretary of state and attorney general; if a candidate like Pennsylvania state Sen. Doug Mastriano (R) wins in the future, it seems less likely that this type of suit would be enforced. Even if lawsuits are filed to ensure accurate results, it halts the process and undermines trust in elections. Imagine if this clash took place after the 2020 general election, bringing a whole election to a standstill for two months, or if the contested ballots actually made a difference in who won.

In June, we saw the first high-profile incident of officials failing to submit results this election cycle. In Otero County, New Mexico, three Republican commissioners refused to certify their county’s primary election results. The basis for the refusal was a belief in unfounded, conspiratorial claims about the security of Dominion Voting Systems machines. After the New Mexico secretary of state sued and the state Supreme Court ordered the county to certify, two of the three commissioners finally complied.

Michigan Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson (D) called the Otero County crisis “the first shot across the bow, indicating to all of us what is going to be a very real strategy.” But, Otero County’s intransigence was also extreme and ridiculous (one of the commissioners is the founder of “Cowboys for Trump” and convicted for trespassing into the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021). That also makes it easier to discount as an illegitimate, one-time event.

In contrast, the standoff in Pennsylvania has a veneer of legitimacy — without understanding how undated mail-in ballots are timely and valid, it may sound acceptable for election officials to discard them. However, election officials can’t ignore court orders and settled law to choose their own preferred scheme of which ballots are “valid” and which are not. This impasse in Pennsylvania will soon be resolved, but it’s the clearest warning sign we’ve seen of what’s to come.