Wondering How Ranked-Choice Voting Works? You’re Not Alone.

The New York City mayoral primary is coming up this Tuesday, June 22, and with it will come one of the most high-profile uses of a new voting reform: ranked-choice voting. In today’s Explainer, we walk through how ranked-choice voting works, where voters can expect to see it on their ballot and what it means for election outcomes and voting rights.

How does ranked-choice voting work?

For most elections in the United States, voters pick just one candidate per office on their ballot. Usually, the candidate with the most votes wins (unless there is a run-off to ensure the winner secures at least 50% of the vote, like in Georgia’s Senate races this year). This is called a plurality election, and it’s how most Americans vote. However, in instances where there are more than two candidates in a general election, this winner-takes-all approach means that some votes are “wasted” — and the preferences of the voters who backed losing candidates are completely ignored in the final result. Ranked-choice voting is a solution to this problem.

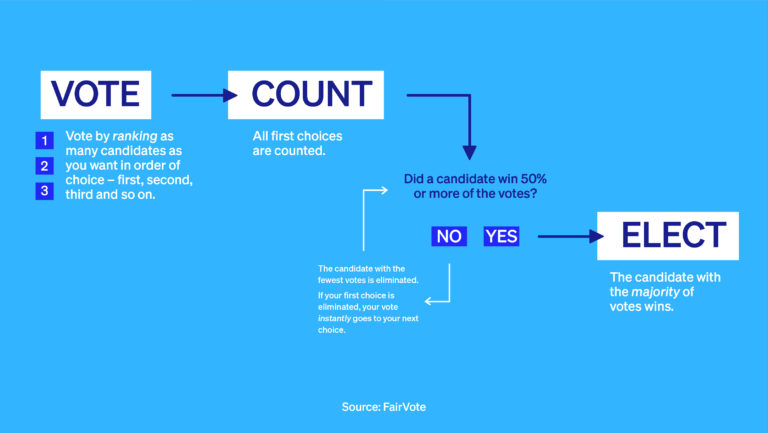

In ranked-choice voting systems, voters rank multiple candidates on their ballot according to preference. If no candidate wins at least 50% of the vote right off the bat, ranked choice elections follow a different process than plurality elections. Let’s say a voter selected three candidates on a ballot, in order of preference: candidates A, B and C. The voter likes candidate A the best and wants them to win, so they put them first on their ballot. Candidates B and C are the voter’s second and third choices — meaning they like them more than any remaining candidates like D or E.

While it varies by state, here’s the basic principle of ranked-choice voting: If no candidate gets over 50% of the vote after counting every voters’ first preference, the candidate with the lowest vote total is eliminated. Then, the second preference of those who voted for the eliminated candidate is counted. This vote transfer process allows the voter to get a say in the remaining candidate choices even if their first choice did not get enough votes to stay in consideration. Ranked-choice voting allows voters to cast a ballot for candidates who finish last if that is their first choice — but still have their preferences between the remaining candidates considered in the final vote count. This process of eliminating and recounting continues until one candidate gets over 50% of the vote and a winner is declared.

What states currently use ranked-choice voting?

There are dozens of jurisdictions across the country that have embraced ranked-choice voting, and dozens more that expect to use it for the first time in their next elections. This is the first year that New York City’s mayoral primary election will use ranked-choice voting after New Yorkers approved a 2019 ballot measure to institute the change. Maine used ranked-choice voting for all statewide and presidential general elections in 2020 and plans to extend its use to primaries in 2024. Alaska enacted ranked-choice in 2020 and starting in 2022, it will be used for all statewide and federal elections in the state. Seven states including Georgia employ or plan to employ ranked-choice voting for military and overseas voters in run-offs, starting next election. Nevada, Kansas, Wyoming, Alaska and Hawaii used ranked-choice voting for some aspects of their 2020 presidential primary elections. And jurisdictions in fourteen other states use ranked-choice voting in their state and local elections, including Florida, New York, Massachusetts, Michigan and California.

Ranked-choice voting is also widely used outside of the United States, with jurisdictions in Australia, Ireland, New Zealand, Malta, Northern Ireland and Scotland all using the system for various elections. Party elections in the U.K. also employ the method, as well as elections for some levels of office in India, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

What does ranked-choice voting mean for our elections?

Ranked-choice voting, political scientists believe, could bring about much-needed change to our elections, and how voters approach their decisions at the ballot box. First, it encourages candidates to be more civil to one another and to form alliances when possible — because being the second choice candidate for another’s supporters is extremely beneficial on a ranked-choice ballot. For example, in the 2020 Senate race in Maine, Independent Party candidate Lisa Savage told her supporters to rank Democrat Sara Gideon second on their ballots, so that when Savage was eliminated from consideration, her supporters’ votes would go to Gideon to increase her odds against Republican Senator Susan Collins. This type of collaboration and explicit statements of allyship can make the day-to-day dynamics of campaigns more civil and deliberative.

Second, ranked-choice voting encourages voters to actually vote for their first choice candidates — even if they have a slim path to victory. That’s because if their candidate is eliminated, their votes go to their second choice, and are not “wasted” on a candidate with no shot of winning. This opens the door for third-party candidates to establish a stronger presence in elections since a Green Party candidate wouldn’t be splitting votes with a Democrat who may have a better chance at beating the Republican.

Ranked-choice voting can improve the behavior of candidates and increase the power of voters to see their preferences elected. Advocates believe that enacting ranked-choice voting for elections across the country would significantly strengthen our democracy, revitalize voter participation and minimize voters’ feeling that they must choose the “lesser of two evils” when headed to the ballot box.

New York City’s mayoral primary election on Tuesday will be a significant test of how voters and candidates feel about ranked choice — and perhaps inspire adoption of the method throughout the rest of the country.