Federal Judge Strikes Down Galveston County, Texas Commissioners Court Districts for Violating Voting Rights Act

WASHINGTON, D.C. — On Friday, Oct. 13, a federal judge struck down the districts for Galveston County, Texas’ commissioners court — the county’s primary governing body — for diluting Black and Latino voting power in violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act (VRA).

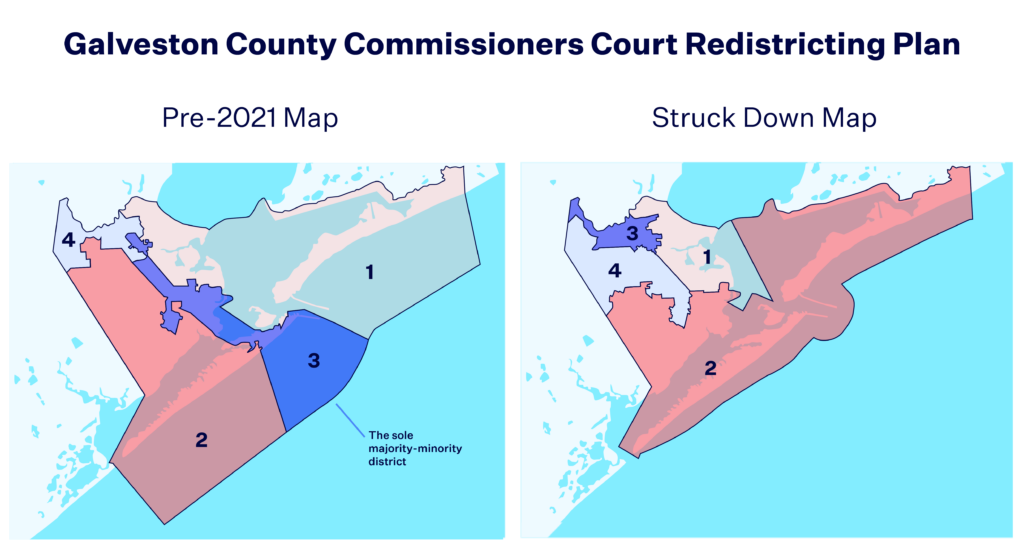

This resounding voting rights victory stems from a 2021 consolidated federal lawsuit brought by voters, civil rights organizations and the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) that went to trial in early August. Together, the plaintiffs alleged that Galveston County’s commissioners court map drawn after the 2020 census — which dismantled the county’s sole, longstanding majority-minority precinct — violated both Section 2 of the VRA as well as the U.S. Constitution’s prohibition on intentional discrimination and racial gerrymandering.

In today’s 157-page opinion, Judge Jeffrey Vincent Brown, a Trump appointee serving on the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Texas, ruled in favor of the plaintiffs’ Section 2 claim, but declined to reach a decision on the racial gerrymandering or intentional discrimination claims.

Brown found that the “the enacted plan illegally dilutes the voting power of Galveston County’s Black and Latino voters by dismantling Precinct 3, the county’s historic and sole majority-minority commissioners precinct,” which remained in place from 1991-2021.

As the opinion explains, the challenged redistricting plan divided the county’s Black and Latino voters — who account for nearly 40% of the total population — among all four commissioners’ court precincts. Because “those minority voters have been subsumed in majority Anglo precincts,” where political preferences of the county’s minority voters significantly diverge from those of white voters, Black and Latino voters would not have been able to elect their candidate of choice in any one precinct.

Throughout his opinion, Brown chronicled how the 2021 decennial redistricting process marked the first time in nearly four decades that Galveston County was free to alter its redistricting plans without federal oversight as a result of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2013 decision in Shelby County v. Holder.

Prior to the 2021 redistricting process, the county was subject to federal preclearance requirements under Section 5 of the VRA. As a jurisdiction with a sordid history of racial discrimination, the county was required to submit proposed changes to its redistricting plans and voting laws to the DOJ or a federal court for approval. Brown noted that on six separate occasions between 1976 and 2012, the DOJ objected to various Galveston County redistricting and election proposals. “Although Galveston County is no longer subject to preclearance, the defendants still must comply with the edicts of [Section 2],” the opinion reads.

Brown also described the significance of Precinct 3’s rich history of coalition-based minority electoral power against the backdrop “of ongoing discrimination affecting Black and Latino voting participation.” The opinion underscored how both past and present “discrimination against minorities in Galveston County harms their ability to participate equally in the electoral process” and perpetuates “[r]acial and ethnic disparities in education, income, housing, and public health.”

In addition to concluding that the plaintiffs satisfied all of the factors needed to prevail on a Section 2 claim, Brown highlighted how the commissioners court rushed the 2021 redistricting process and failed to consider any meaningful input from the public or from Precinct 3’s former Black representative, Stephen D. Holmes. Commissioner Holmes had represented Precinct 3 since 1999 and was the court’s only Black member at the time of the 2021 redistricting process. “[I]t is stunning how completely the county extinguished the Black and Latino communities’ voice on its commissioners court during 2021’s redistricting,” Brown wrote.

Towards the end of the opinion, Brown rebuffed the Republican commissioners’ arguments calling into question the constitutionality of Section 2 of the VRA, reminding them that a “five-justice majority” of the Supreme Court recently upheld Section 2 in Allen v. Milligan.

Brown emphatically concluded:

This is not a typical redistricting case. What happened here was stark and jarring. The commissioners court transformed Precinct 3 from the precinct with the highest percentage of Black and Latino residents to that with the lowest percentage.

Acknowledging that “Galveston County’s 2024 elections are imminent,” Brown ordered the commissioners court to submit a remedial plan that complies with Section 2 of the VRA and contains at least one majority-minority precinct by Oct. 20, 2023. The order states that if the “defendants fail or prefer not to submit a revised plan,” then they must implement a plan submitted by one of the plaintiffs’ experts by Nov. 1, 2023 for use in “all future elections until the commissioners court adopts a different plan.”

In a press release from the UCLA Voting Rights Project, Bernadette Reyes, one of the attorneys on the case, spoke to the reverberating nature of the decision: “The implications of this decision extend beyond the borders of Galveston County. The ruling sends a clear message to jurisdictions nationwide: Redistricting efforts that marginalize minority communities, whether out of malice or negligence, violate the fundamental pillars of our democracy and will not be tolerated.”