Redistricting Rundown: Georgia

Georgia’s General Assembly finished drawing new congressional and legislative districts last month, although Gov. Brian Kemp (R) has yet to sign them into law. This year, Republicans fully controlled redistricting, just as they did in 2011 after the previous census. But the Georgia GOP had to contend with a very different Georgia this year. While the state was solidly Republican at both the state and federal levels in 2011, the tables turned after President Biden became the first Democrat to carry the state since President Clinton in 1992. Georgia is now firmly in swing-state territory. In response to these political changes, Georgia Republicans used redistricting to try to maintain their political control in the state. But while the new districts will likely bolster Republicans in the short term, Republicans ultimately face an uphill battle against the broader trends changing the state.

Georgia’s political and demographic landscapes are rapidly changing.

Over the last decade, Georgia’s population has both grown rapidly and become increasingly diverse. Since 2010, the state’s population has increased by over a million people, with growth concentrated in the Atlanta metropolitan area while rural areas lost population. At the same time, the population has diversified, with the share of residents who identify as white and non-Hispanic shrinking to just 50%, the lowest on record. The diversifying trends are especially notable in Atlanta’s suburbs, with multiple suburban cities like Johns Creek in Fulton County and Peachtree Corners in Gwinnett County all becoming majority-minority communities for the first time even as the white population of Atlanta itself increased.

The influx of college-educated voters from other states and a rising nonwhite population in the Atlanta area have fueled a pro-Democratic trend in the state, as both of these groups tend to support Democratic candidates. Although the state has been under Republican control since 2005, Democrats have become increasingly competitive in elections at all levels of government. In 2016, Trump carried the state by the lowest margin for a Republican since 1996 and in 2020 President Biden became the first Democrat to win since 1992. Likewise, Democrats flipped two suburban Atlanta congressional districts, won both of the state’s Senate seats in runoff elections earlier this year and increased their numbers in both houses of the Georgia General Assembly in the last two elections.

The new districts attempt to preserve Republican advantages in the state.

Republicans’ primary goal in Georgia this year was to cement their hold on political power for another decade. But to do so, Republicans had to directly contend with the trends reshaping the state. Since population growth was concentrated around Atlanta, more of the state’s legislative and congressional districts have to be anchored in the Atlanta area — the exact region also fueling the state’s pro-Democratic trend.

Ultimately, Georgia Republicans had to cede some ground to Georgia Democrats to maintain their advantage by packing Democratic voters into more districts to make the remainder safer for Republicans. The new state Senate map, for example, shifts two rural Senate districts to heavily Democratic-parts of the Atlanta area. Likewise, Democrats could gain upwards of six seats in the state House under the new districts. In exchange, the remaining districts have fewer Democratic-leaning voters that could make elections competitive for Republican incumbents.

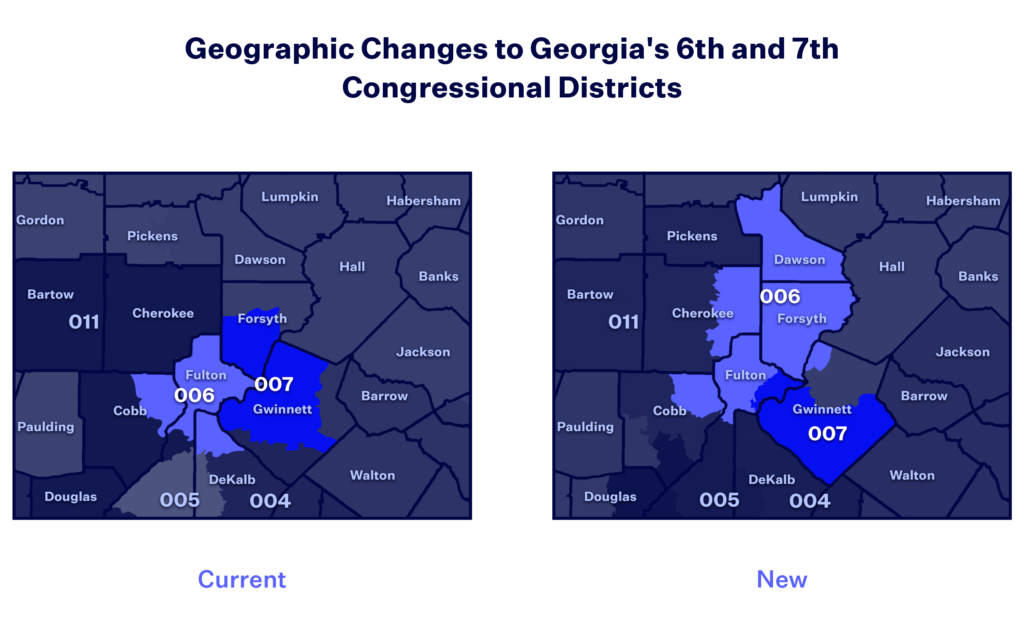

Republicans used the same approach for Georgia’s congressional districts, with the most drastic changes reserved for Georgia’s 6th and 7th districts, the most competitive in the state. The 6th District, which in a past iteration was represented by former Speaker Newt Gingrich (R), was first won by Rep. Lucy McBath (D) in 2018, while Rep. Carolyn Bordeaux (D) flipped the 7th in 2020 after coming up just 433 votes short in 2018. Under the new plan, the 6th District sheds Democratic portions of Fulton and Dekalb Counties in exchange for the more rural and Republican Forsyth, Dawson and Cherokee Counties. The 7th District, meanwhile, sheds its portion of Forsyth County and becomes almost entirely based in Gwinnett County.

The result is a more Republican-leaning 6th District and a more Democratic 7th — turning two competitive districts into two comparatively safe districts for both parties. In recognition of these changes, Rep. McBath has decided to challenge Rep. Bordeaux in the new 7th, now one of the most diverse districts in the country with no single majority racial or ethnic group. These changes were criticized by Democrats like State Sen. Michelle Au (D), who pointed out the current 6th is within 1,000 people of the target district size and didn’t require significant changes. Rather than risk the two seats continuing to trend away from Republicans, the Georgia GOP conceded one safe Democratic district in exchange for making a safer Republican seat, just as they did with the state legislative maps

Georgia’s new maps demonstrate how redistricting can only delay, not stop, political trends.

While Georgia’s new maps will likely preserve Republican advantages in the state for the next few years, they will not be able to halt the broader trends changing the state’s politics. The suburban counties that powered President Biden and Sens. Ralph Warnock (D) and Jon Ossoff’s (D) victories are growing rapidly and the state’s leftward trend is likely to continue. This month alone, Democrats netted more than 30 seats in statewide municipal elections. The artificial lines created by Republicans may not be able to withstand these changes forever.

The new configuration of the 6th District illustrates this reality quite succinctly. While Trump would have taken 56% of the vote in this district had it existed in 2020, Mitt Romney won 70% just eight years before in the 2012 general election. The district’s demographics also reflect the broader changes in Georgia, with the white population falling from 73% to 64% and the Asian population doubling since 2010. While unlikely to be competitive next year, by the end of the decade it could become winnable for Democrats again. Ironically, this is exactly what happened last decade, as the old version of the 6th District was also originally drawn as a Republican seat — giving Romney 60% of the vote in 2012 — only to see it fall into Democratic hands within six years.

Gerrymandering can act as a stop-gap measure, but it cannot stop a district (or a state) from turning blue indefinitely. Fiddling with district boundaries does nothing to stop a population from growing or diversifying, nor does it prevent voters from switching political parties. Republicans will be able to use gerrymandering to preserve their hold on Georgia for now, but at the rate the state is changing, the next redistricting cycle could look a lot different.