Louisiana at the Forefront of the Fight To Save the Voting Rights Act

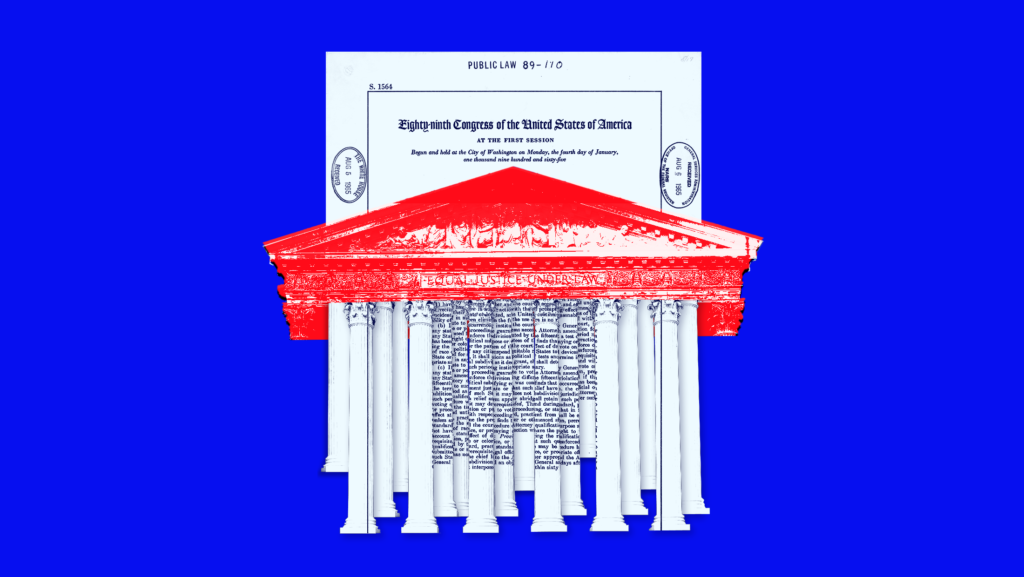

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) might be the most consequential piece of legislation passed in the United States in the past 100 years. It’s certainly the most important civil rights legislation of the last century. Yet, next term, the six conservative justices on the U.S. Supreme Court could gut what remains of it when deciding a case out of Alabama, in a ruling that will almost certainly impact my home state of Louisiana and the future of the VRA itself.

Amid a string of controversial rulings in June, the Court’s conservatives reinstated Louisiana’s congressional map. In doing so, they blocked a ruling from a federal judge in a lower court that ordered the Republican-led Legislature to redraw the map it passed in February on the grounds that the previously blocked map likely violated Section 2 of the VRA by diluting the voting power of Louisiana’s Black residents. The justices issued their opinion on the Court’s “shadow docket,” which allowed them to rule without explaining their reasoning. All three liberal justices dissented. The Louisiana case is now paused pending the Supreme Court’s decision in the similar redistricting case coming out of Alabama.

For the past decade, only one of Louisiana’s six congressional districts has been majority-minority, despite Black residents accounting for more than 33% of the state’s population, while the other five districts have been overwhelmingly white. Since Black Louisianans make up one-third of the state’s population, this creates a simple equation that advocates, organizers, civil rights lawyers, elected officials, and citizens repeatedly hammered on in the months leading up to February’s special legislative redistricting session: one-third of six is two, so there should be two majority-minority congressional districts.

Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards (D) agreed, vetoing the map the Legislature enacted that kept the same 5-1 scheme intact. The Legislature then overrode his veto, setting off a series of court battles that ended up with Louisiana’s map before the Supreme Court.

Though the action around Louisiana’s congressional map has been relatively fast and furious during the first half of 2022, the groundwork for the court battles was laid over the course of a couple years. A coalition of advocates, including my organization, Louisiana Progress, as well the ACLU of Louisiana, the Power Coalition for Equity and Justice, Black Voters Matter, the Southern Poverty Law Center, and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund (LDF) spent much of 2020 and 2021 organizing people all over Louisiana — in person, when COVID-19 restrictions allowed, and online — to fight for maps that fairly and accurately represented the state’s racial diversity. In contrast, Louisiana’s Republican leadership worked almost entirely behind closed doors to pursue their own ends.

In the months leading up to the February redistricting session, the legislative committees in charge of the process held a 10-stop roadshow, with events in every corner of the state. At each one, dozens, if not hundreds, of Louisianans showed up to ask the legislators to create a second majority-minority congressional seat. Proposed maps were submitted showing how it could be done, including seven by LDF. There was an obvious groundswell in favor of increased racial representation.

Aided by the same national conservative political interests that spent decades stripping away provisions of the VRA, Republican lawmakers, in our view, wanted to use Louisiana to enable the Supreme Court’s conservative majority to gut the most important remaining element: Section 2.

However, as the special session approached, it became increasingly clear that the majority of legislators weren’t interested in following the census data or the people’s will. During the final roadshow hearing, at the state capital in Baton Rouge, some Republicans on the committee expressed outright hostility toward the idea of a second majority-minority district. Once the session started, that hostility became even more blatant.

During the years of organizing leading up to redistricting, I often heard some variation of the same question from concerned citizens. They asked, “Why should we put any effort into redistricting when we know those legislators are just going to do whatever they want to do?” The only answer I could offer was to say that all we could do is fight our fight and hope for the best. It was certainly better than not fighting at all.

While I still believe that sentiment to this day, it was apparent throughout the redistricting session that those legislators were indeed going to do whatever they wanted to do, without concern for the census data or the expressed will of the people. The entire three-week session was a steamroll, with the Legislature passing congressional and state legislative maps that clearly violated the VRA, while also making no effort to increase racial representation in any other statewide political body.

During the session, local journalists also revealed that Republican legislative leaders had contracted with a national law firm, BakerHostetler (which is known for assisting conservatives in redistricting lawsuits), to advise them. The reason it had to be reported was because the leadership kept the contract hidden from most of the Legislature.

With every passing day, it became more and more obvious that Republicans wanted to go to court. Our hunch? It had been their plan all along. Aided by the same national conservative political interests that spent decades stripping away provisions of the VRA, Republican lawmakers, in our view, wanted to use Louisiana to enable the Supreme Court’s conservative majority to gut the most important remaining element: Section 2, which prohibits state and local government from imposing any voting rule that “results in the denial or abridgement of the right of any citizen to vote on account of race or color” or membership in a language minority group.

And the state Legislature wasn’t the only culprit in that plot. Local political bodies, particularly the school boards in two of the largest parishes (in Louisiana, we use “parish” instead of “county”) in the state, Jefferson and East Baton Rouge, also passed maps that don’t accurately reflect their racial demographics. The populations of both parishes are majority-minority, yet only two of the nine school board districts in Jefferson and three of the nine school board districts in East Baton Rouge will be majority-minority.

While we don’t know how the Supreme Court will rule in the Alabama case next term, the conservative justices, and the movement they represent, could finish off the VRA, and do so at all levels of government, ending the most important legislative step toward civil rights that our country has taken in the modern era. While we didn’t get the outcome we wanted in Louisiana, and what millions of Black Louisianans deserve, the battle is far from over. As Republican state lawmakers, right-wing “activist” groups and the hyperconservative Supreme Court continue to undermine our democracy, we can’t — and won’t — give up.

Peter Robins-Brown is the executive director of Louisiana Progress.